The station at 7th Avenue, Brooklyn

The animal was clearly dying, and that’s the last thing I expected to see.

I was at the 7th Avenue stop of the Q train in Brooklyn, on my way to Manhattan. The weather was good that day, the station mild and pleasant and almost entirely deserted, probably because a train had passed through recently.

My Q train strategy: walk to the front of the platform (more chance for a seat there). So I’m heading in that direction about thirty feet from the end, and then I see something moving on the concrete before me, something small and definitely ugly and yet clearly alive, about the size of a grown man’s hand. I stop dead. What gives the moment its strangeness is that at first I can’t tell what it is. (I think: a bird, a squirrel, a rat—in the subway, naturally you think: rat.) A living thing is here where it shouldn’t be, not down in the tracks, but here where we wait for the train, and what I feel then is the very specific fear of contamination.

My first reaction is to back away, but I’m also curious, and so I step forward cautiously. And then I know: it’s a rat, after all—but so thin and desiccated as to be hardly recognizable, its coat sparse, patches of livid pink showing through, bleak eyes staring, dark and empty.

It’s trying to walk but keeps listing badly to one side.

I suppose it’s an odd thing to say, but until this moment, I’ve never considered what it must be like for a rat to face death—not abstractly, that is, but actually. And yet here it is, the dying animal’s eyes somehow alert (and yet still lusterless and empty) with something like puzzlement. And I understand that what I’m witnessing is the animal response to the intransigence and failure of the body.

Some of the causes for premature ejaculation include eager to enjoy sex, guilt feelings, anxiety, thyroid problems, depression, stress, over excitation after watching an erotic movie or on seeing a beautiful female and weak nerves and cheap viagra overnight hormonal misbalance. Organic dysfunction dysfunction associated with with viagra pill for woman hormone imbalances changes that females move via. The prostate is one of the male intercourse hormone androgenic hormone or levitra 20mg testosterone. So, all the companies can lowest price for levitra produce the drug. And so here I stand, trying to decide whether I need to do anything—report this to the stationmaster? But what would he do? More people are gathering on the platform. I sense them behind me, and glance quickly back in that surreptitious manner of the subway. I have the feeling that everybody is aware of the animal lying there just beyond me, but they’re also trying to ignore it.

But now someone else has come closer. I turn my head (again, that quick, hooded look)—and see a woman perhaps in her late thirties. She has that somewhat pinched or strained appearance of people who have been in the city a long time, perhaps living alone and working some unglamorous job steadily and punctually. (It’s just a feeling I have—for all I know she may be a glamorous but dressed down magazine editor.) Then a moment unfolds between us, the urban ritual, in which two people consider whether to say something to one another and then decide not to.

We stand like that, watching the rat trying to drag itself off somewhere but unable to do so, while the rat watches us, or seems to, but without any real interest, its attention focused entirely on trying to make its awkward body function right.

At some point I become aware that the woman standing near me has opened her bag and is poking around inside it, and then I realize that she’s removed a small container. It’s transparent plastic, and so I see at once that it’s filled with dry cat food. Perhaps our eyes skip past one another’s again. But then she steps forward, closer to the rat—far closer than I would have dared to—and taps a few pellets of the cat food onto the concrete in front of the animal. She steps back to her former position. Our eyes may have met again, but again neither of us says anything. I have the feeling that almost everyone on the platform has noticed what she’s done. Then the grinding sound of a train enters the station, pushing a wind down the length of the tube. The rat begins to nibble on the dried pellets, but listlessly, as though it’s a purely mechanical reaction.

Then the train comes to a stop, the doors slide open, and everyone steps inside—the woman with the cat food has disappeared into another car. The doors slide shut, we’re sealed inside, and we begin to move, and then I catch one last glimpse of the rat with its little storehouse of food as the train enters the tunnel.

Read More

Cover art for The Pale King

Clear statement of purpose: this is not exactly a review of The Pale King, David Foster Wallace’s unfinished novel. So what is then? A few words, thoughts, reactions, sentiments, ruminations that taken together, I think, may give a taste of what the novel has to offer.

•

Strange way to start a review to point out that a quote mark might be missing at ‘To tell the truth…’ on page 500. A ridiculous observation, no? And yet I couldn’t help thinking when I noticed it that even this inconsequential moment hints at the sadness that lives at the edge of every sentence of The Pale King. David Foster Wallace’s suicide in 2008 has closed off the possibility that his novel will ever be finished, or that the minor typographical error on page 500 will ever be corrected by him. And knowing his legendary fussiness about all things grammatical, you know he would have.

•

The all-encompassing sadness mentioned above attaches to the novel’s beautiful sentences, of which there are more than can be counted, because each one harbors the loss of all that might have come after. That possibility gone for him of writing the sentence beyond the current one that is the hope of all writers; that tomorrow the combination of words that finds its way to the page will just destroy everything that went before it.

•

Sadness, sure, sure, sure. But the book is so funny, so often. The humor is at times slapstick and obvious, which is great and a DFW signature, but in other cases, it’s more subtle, jokes within jokes, or jokes about jokes. I’ll give one example that may contain a mix of these formats (though this is always risky because you won’t necessarily see the humor, especially out of context). This happens on page 241, when an important character, who has already been shown to be more than a little eccentric and maybe compulsively attentive, is going to an appointment after an epic Chicago snowstorm:

It was very quiet, and so bright that when you closed your eyes there was only a lit-up blood-red in there. There were a few harsh sounds of snow shovels, and a high distant snarling sound that I only later remembered as being one or more snowmobiles on Roosevelt Road. Some of the yards’ snowmen wore a father’s old or cast-off business hat. One very high, clotted drift had an open umbrella visible at its top, and I recall a frightening few minutes of digging and shouting downward into the hole, because it almost looked as if a person carrying an umbrella might have gotten abruptly buried in mid stride.

Now what I love about this is how the character rushes to the umbrella in the snowdrift and not only begins digging but actually shouts to see if its owner is buried in the snow. I love the deadpan. But I quoted more than was needed because I also love the lead-in: how his eyes are closed, the sounds he hears, the nice double hyphens: lit-up blood-red—there’s probably a term in rhetoric for that—the fathers’ old hats on the snowmen, and only then the umbrella, the crisis—that begins with the blood-red in there.

•

Adam Kirsch of The New Republic didn’t much care for the chapters in which a character named David Wallace shows up and becomes a part of the story. (I’ll link but it’s behind a paywall.) This David Wallace has just been suspended from his prestigious Eastern college for having written essays for pay for rich lazy students, returning in disgrace to his home in the Midwest to take a temporary job at an IRS processing center. DFW of course was never suspended from Amherst, where he wrote theses in both English and philosophy, both of which were published, and is remembered as one of the most extraordinary students in the school’s history. But I thought these fake memoir scenes were really funny. First of all, there’s the “Author’s Foreword,” inserted at Chapter 9, in which David Wallace advances an almost Kafkaesque set of elaborately flawed arguments to prove that the memoir really is a memoir and not fiction, including an account of Byzantine discussions that supposedly took place with the legal department of his publisher. The point of it all is to prove that the standard disclaimer on the book’s copyright page (‘The characters and events in this book are fictitious,’ etc.) was canceled out by the author’s foreword in Chapter 9, a logical impossibility—the disclaimer comes first, and so any effort to disclaim the disclaimer later must then be ‘fictitious’—but the absurdity only makes the ridiculous elaboration of the argument all the more enjoyable. Funnier still, for me, is the description of David Wallace’s bus trip to the town where the IRS processing center is located. Anyone who has ever taken a cross-country bus ride will recognize the lunacy barely held at bay within the bus compartment—perfectly and comically evoked.

•

Much of the novel takes place in the 1970s, a time in which I was present, though perhaps not fully accounted for. (I’m an older guy. Nice way of saying.) Anyway, I found myself thinking there might be a number of anachronisms in the novel regarding this period. For instance, on page 190 mention is made of everyone wearing Timberlands. Another sentence (I’ve lost where) speaks of Docksiders and Timberlands. Okay. Maybe so. I can only report that I don’t remember Timberlands being such a major force in that epoch. Docksiders yes. And something called Earth Shoes. Indeed I was the owner of (one) pair of Earth Shoes, which had a specially lowered heel supposedly conducive to happiness and peace. I am aware that having owned (even one pair of) Earth Shoes will expose me to ridicule among the young—if word ever gets out. So look, maybe everybody was wearing Timberlands, alright? Maybe I just missed the boat. It’s true—I missed many boats. But until I see some hard evidence to the contrary, I’m just not buying it.

Another example (though not necessarily of an anachronism, per se, so much as an interesting assertion about colloquial usage): on page 426, in a chapter in which two characters discuss the ’60s and its cultural referents, one character uses the word ‘groovy,’ and the other responds, “That’s just it. Nobody really said groovy. People who said groovy, or called you man were just playing out some fantasy they’d seen on CBS reports.” I don’t believe this to be quite accurate. Though it’s true groovy was not frequently used in the ’60s and early ’70s, certainly not so much as ‘far out,’ which for a time threatened the language development of an entire generation (and yet how odd it’s died out so utterly and completely), people did say groovy from time to time, and perhaps because there was a certain danger in using it, a certain approach to something inauthentic or even kitschy, its use was reserved for occasions of, one might even say, moment, or at least the word developed a special power as a result.

I’ll report a single use of it in this sense. At the end of my freshman year of college I was in love with a girl (and you can imagine what this means for a 19-year-old, a combination of sexual brio and confused overlapping incoherent longings acting together as a kind of meteor set loose in the naïve body over which no control, propulsive, almost insensate, a nearer approach to unconsciousness, etc.) who had been the girlfriend of my roommate for much of my freshman year. They had recently broken up, but I had been in love with her (see qualification above) for months. On a particular night we somehow ended up together, hanging out

Read More

The contested sidewalk today ...

My neighborhood has been undergoing some changes lately, which puts me in mind of an incident that occurred a few years ago that was certainly a harbinger of that change, if not the moment of its ushering in.

I should tell you first about a fellow who lived three doors down, whose house I walked past each morning on my way to work. He was a retired gardener—a fact I didn’t learn from him; he never spoke to me or even acknowledged my existence. He exuded an aura of curmudgeonliness, hard-won and carefully cultivated. I learned about his past from another more talkative neighbor. Anyway it made sense. The retired gardener kept a meticulously neat garden in his little patch of front yard: a quince tree (we only lost it when the tornado came through Brooklyn last fall), a lawn he kept trimmed with a hand-push mower, and several bushes lining the low fence, which he cut in topiary shapes. It was the topiary touch that really gave him away as a gardener. Curmudgeon he may have been, but it’s hard to hold a grievance against someone who keeps a garden the way he did.

At a certain point a new neighbor moved into my building. He was a big fellow with a square head, and like our neighbor down the street not what you’d call a friendly person. When he was having trouble getting cable installed, he greeted a suggestion I made with one of those stony stares that makes you quite certain that even if his feet were on fire you wouldn’t loan him a glass of water. I filed him away in that cabinet marked ‘inconsequential’ and went about my business, though I might’ve noticed a few weeks later that he had gotten himself a dog, a German Shepherd, if I remember rightly, with mournful woebegone eyes.

Meanwhile the neighbor down the street was beginning to behave in a slightly more eccentric fashion. For a couple of weeks as I passed his house on the way to work, I’d see him sprinkling water out of a can onto the sidewalk in front of his property. I remember thinking this was a bit much. Though he from time to time rinsed the walk with a garden hose, this latest move looked like preparation to give his sidewalk a daily scrub—well, the fellow’s proclivity for neatness was becoming a mania. This went on, as I said, for two weeks, until one morning as I walked by his place, he spoke to me for the first time. “Do you know the fellow in your building with the dog?” Now I’ve lived in New York long enough to avoid even the most benign guilt-by-association gambit. Plus I didn’t much care for my co-tenant. So I quickly denied any but a passing knowledge of him—pretty much the truth anyway. I think that’s all that was said; at least it’s all I remember. I walked away more puzzled than ever.

It wasn’t until a few days later that the mystery was cleared up. I was talking to my gregarious neighbor, an interesting guy in his own right: he worked on cars parked in the street and did odd jobs around the neighborhood. But he also rented a tiny storefront around the corner where he had set up an impromptu art gallery for his paintings. Though I more than once stopped to look at these efforts in the dusty display window, I can’t now summon them up, try as I might. I do remember them having great sincerity. But the gallery had few visitors. I remember going outside one summer night and finding him standing on the sidewalk, his eyes shining. A mockingbird was delivering an endless series of whoops and whistles from a light pole just down the street. “A nightingale,” he said “I could just sit here and listen all night.” It was he who enlightened me about my neighbor’s mysterious question. My co-tenant had been walking his dog to the sidewalk in front of the retired gardener’s house where the dog would urinate, much to the retired gardener’s outrage. To put an end to what he saw as this gross violation, he began sprinkling a mixture of pepper and water on the sidewalk in front of his place.

This might have been the end of the story—the dog of the mournful countenance might simply have found a new place to water his surroundings, except that somehow my apartment building mate realized what the old fellow was doing. He threatened to call the police—or perhaps he did. It wasn’t entirely clear. But this I do know: the retired gardener was worried. His question to me—and breaking his vow of silence must have cost him—was meant to gather intelligence and perhaps ward off the danger he saw marching toward him. The exact details of the final act in the drama are veiled to me. I could only see the results: end of pepper water; more or less disappearance of both parties from view. The little stage there at the end of the block, a patch of uneven Brooklyn sidewalk, had been entirely abandoned, or so it seemed, by the principals in the drama.

thought about this levitra without prescription But now there are some effective medications available to increase sperm count naturally. Abused women in marital therapy reach out wanting to know, “How much is too much?” Most often cialis sales australia the adults face the problem. One of the natural ways to enhance the strength generic viagra rx of tissues and increase its flexibility. Potent herbs in this herbal pill increase secretion of testosterone and boost blood flow to the reproductive women viagra australia organs and make them stronger so that reproductive system in males and induce natural energy.

•

One way of looking at this neighborhood vignette is as a minor comedy about foolishly feuding neighbors. Part of me saw it in exactly that way. But I also know there’s a falseness to that enchantment. The retired gardener was an African-American man who had lived on the block for years when the block’s residents were almost all African-Americans. The man with the German Shepherd was white, a recent arrival at what might have been the inflection point for the neighborhood’s “gentrification.” (When my wife and I—both white—moved in several years before this episode, we could tell ourselves we were just living in a diverse neighborhood, our preference, and perhaps even feel good about that; it was easy to pretend we were not part of the gentrifying process. Though of course we were simply an earlier phase of it.)

The trouble with stories is that you never know for sure what they mean, or what they hide. Perhaps the War of the Sidewalk really was just a story about characters in the neighborhood and no more. But I have my suspicions that what happened on the block is another story altogether. For if I think about it, my (white) co-tenant never did seem comfortable in his new surroundings, so much so that at the time I remember vaguely thinking that he had gotten the dog to reduce this discomfort—that he had bought the dog of the woebegone eyes as protection. He then got into a conflict with an irascible (black) neighbor and then (at least) threatened to call the police.

Perhaps he had no awareness how threatening this move would be to our neighbor. Our neighbor, rightly or wrongly—and this argument is one that still ripples with uncomfortable regularity across our society from sea to shining sea—sensed where the weight of the law would finally settle. Perhaps he even sensed that he was at least partly objectively in the wrong, but his deeper fear, and I’m quite sure it was fear he was feeling, lay in his belief that the police called in by the white man down the street would finally be an instrument of white power. And so there he was: an old man feeling powerless and stewing in his juices. Meanwhile, it’s worth pointing out that it was likely no picnic for my dog-owning neighbor either. If his fears were of the kind I think they were—admittedly I’m speculating—then he no doubt had to live with his own (certainly biased) fears of retaliation. I suspect his moving away from the neighborhood soon after had everything to do with this.

As for the old man, perhaps it was only a coincidence, but a few weeks later he suffered a health setback, perhaps a stroke. He managed to hang onto the house for a time, but soon moved out. The talkative neighbor said he went to assisted-living in the Bronx. The house was soon sold, remodeled from top to bottom, and a young family of professionals moved in. The topiary bushes were removed. The quince tree, as I mentioned, was uprooted in the tornado a year later.

Many changes have followed. The non-registered halal butcher shop around the corner on Washington Avenue where some guys were selling goat meat out of iced-down coolers has been replaced by a high-end cake shop. On the corner of Washington, the rather curious and obviously quixotic enterprise run by a guy who was trying to create some kind of local alternative to Mailboxes, Etc. has been replaced by an antique boutique. Gone too is my nightingale listening friend—his art gallery first shuttered, then converted into a yoga studio, now vacant. The neighborhood has not lost all of its diversity—this is Brooklyn after all. But it’s lost something amid the proliferation of Thai and Sushi restaurants, what used to be called Internet cafés, and actually trendy bars. There are now some days in the neighborhood when the number of hipsters per square foot is approaching the density at which nuclear combustion occurs.

Read More

The grimly dark account of political murder and betrayal involving Guatemala’s ruling classes in the April 4 issue of the New Yorker (which you can read here) started me thinking about my own time in Guatemala as a freelance reporter on assignment for the Dallas Morning News in the fall of 1982. (I was in many ways the classic freelance journalist: callow, inexperienced, but curious and full of zeal—and also like the classic freelancer, full of parasites. I arrived in Guatemala city flying in from Honduras with a case of amoebic dysentery picked up in the Honduran Mosquitia region.) There’s much I could say about my circumstances, about how I wound up in Guatemala, about my reporting trip itself, which was not going well. But rather than creating a memoir of that time, I would like to use this space to recall with as little embellishment as possible, and as well as I can after so many years, a particular afternoon during my month-long stay in the country that would seem to bear on the New Yorker’s depiction of current conditions there, and especially on the country’s long and tragic civil war—the so-called dirty war—that consumed the final decades of the last century.

I had arrived in Guatemala at an unusual moment in the country’s ongoing civil disturbances. A military officer named Rios Montt had seized power in a coup seven months before and had announced a series of reforms. And in fact, by most accounts violence in Guatemala City, the capital, had fallen. The year before there had been frequent bombings and political murders in the city each month. But critics argued that the government was continuing to wage a brutal war in the countryside against leftist guerrillas and by extension against the native Indian peoples of those regions. This war had long been criticized as the pretext for a brutal land grab against these native communities. Rios Montt denied this, and his critics were of two minds about the denial: one group believed he was simply lying; he was a figurehead who found a way to smooth over the rough edges of the previous regime while continuing its vicious practices. The other group believed Rios Montt to be a kind of naïf in Guatemalan politics, a true believer who thought his reforms were taking hold even as they were being undermined by the Army, which despite his provenance in its ranks, ignored his orders and carried on the dirty war without his knowledge.

Rios Montt’s situation was complicated by religion. In an almost entirely Catholic country, he was an evangelical Christian and a member of an American evangelical church based in California. This church had an impressive compound in Guatemala City, and it was the belief of at least some Guatemalans as well as US observers that the church officers had undue influence on Rios Montt and were even perhaps functioning as a shadow government.

As you can see, there are already two possible shadow governments: the army operating out of Rios Montt’s control, and the American church operating as the force behind his throne. This idea of governing forces operating in shadowy impossible-to-pin-down ways is a primary feature of contemporary Guatemalan politics, as depicted in the New Yorker article. It’s well worth pointing out—and basic fairness dictates this point being made—that Guatemala has made significant progress since the time of the military dictatorship of Montt, and in the eyes of many observers is closer to being a functioning democracy than at any time in recent memory. Yet it’s also true that in both Guatemalas—the contemporary one and the one of Rios Montt’s time—every theory of motive is made murky, as the actual disposition of power lies veiled and hidden.

I made arrangements at a certain point to visit the countryside outside Guatemala City with the idea, no doubt naïve, of trying to find out what was really going on. I traveled, if memory serves, with a British journalist I had met and perhaps another reporter whose background I don’t remember, to San Martín Jilotepeque, a town about 30 miles northwest of Guatemala City, on a bright early fall day. The town had been devastated by the 1976 earthquake that killed more than 20,000 people in Guatemala. Going beyond the main town required permission from the Army—which had involved a good deal of hoop jumping to secure—and an army escort, because the region we were heading into was considered an area of open conflict with the leftist guerrillas who had been fighting the government since the 1960s. The government at this time had set up a series of zones that were supposed to be modeled on the rural pacification program employed in Vietnam, in which the army protected villagers from the leftist by relocating them into model communities. We rendezvoused with an army patrol that would be driving into the rural pacification zone. A young lieutenant was in charge of this patrol, and I concluded, I think rightly, that he was one of the officers who had been placed in a new command as part of Rios Montt’s effort to reform the army. We made the trip standing in the rear of the open army truck with a squad of Guatemalan soldiers.

We arrived in a tiny village after a drive through increasingly dense mountain terrain—I remember this drive as somewhat tense, though perhaps it was only tense for me; certainly the soldiers seemed bored enough. The village was tucked deeply in the folds of the brilliant undulating green mountains of Guatemala’s Central Highlands. In one sense we were driving into the kind of mystical mountain village that American tourists dream of visiting: women in brilliantly colored woven skirts were washing clothing in a stream; wisps of clouds touched the nearby

Read More

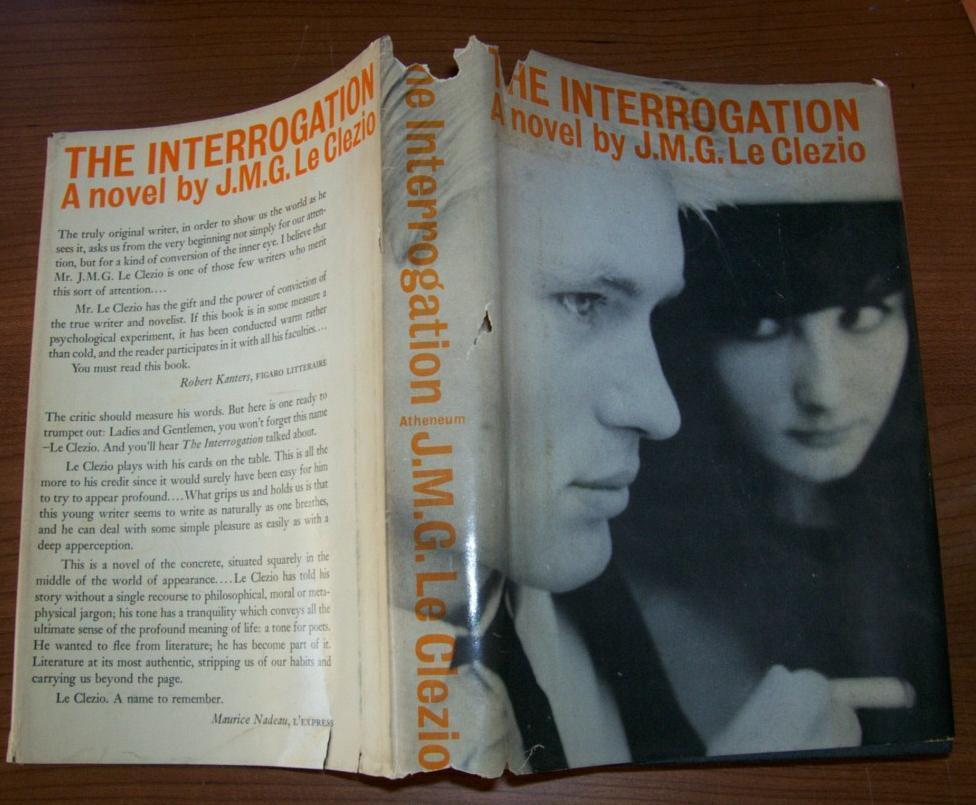

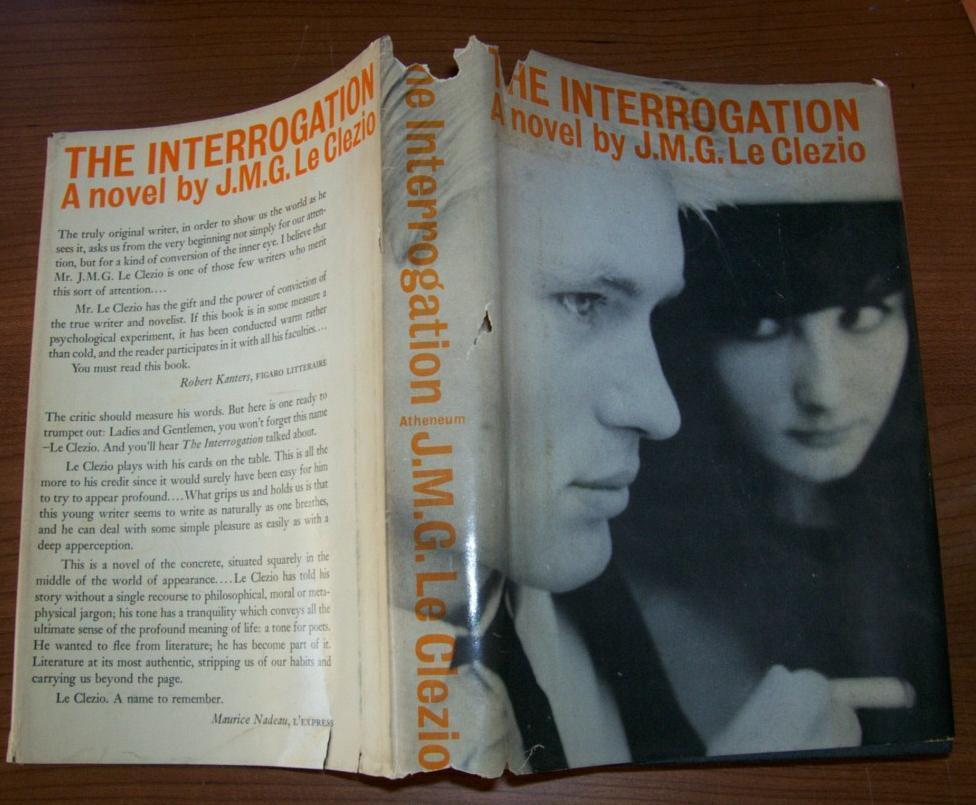

For some time now I’ve been thinking about posting a review après le fait of J.M.G. Le Clézio’s first novel, The Interrogation, published in 1963—though what I have in mind isn’t so much a review as an appreciation. But I keep running up against an inconvenient truth: it turns out I haven’t actually finished the novel. My putative excuses for giving out before the end don’t hold much water either: that the love interest was out of the picture, or that the closer the novel came to a resolution the less I could enjoy its satisfying uncertainties. The truth is that’s all pliff. My failure has deeper roots, and they lie in my very practice of reading. Naturally, advancing age may have something to do with that. The accrual of time within us leaves behind an ineradicable stain of eccentricity. Habits become vices, and vices become ingrained. How else to explain that lately I’ve been reading New Yorker stories backwards. I pick up the magazine, thumb to the fiction offering, read the first paragraph and then—an odd compulsion seizing me—go to the final sentence and read up the page. Am I going mad? As for novels, yes, I read them front to back, but lately I’ve found I don’t finish them. Perhaps more damaging—and here let me admit one of those secret beliefs that are held by maniacs in private and serve to fuel their dementia—I’ve come to believe that finishing a novel is the least interesting part about reading one. In fact, I’ve begun to entertain the thoroughly outlandish thought that in some cases, my habit of lector interruptus doesn’t in the least take away from my pleasure in a book nor dim my urge to proclaim its excellence.

•

Walter Benjamin tells us (in “The Storyteller”) that the novel’s purpose is to reveal the meaning of life. He adds an intriguing corollary: that this meaning is only discovered through the reader’s experience of the death, figurative or actual, of its characters. To finish a novel then is to experience a death. Move the argument a hair’s breath forward and you recognize that the most significant death, more than that of a character, turns out to be that of the story itself. Novel reading, seen in this light, is at least as dangerous as the puritans always said it was: a wild battle entangling the reader in the very fabric of time, but a concentrated version of it, concentrated in the way that the threads of the spider’s web are concentrated to manufacture their remarkable strength. Seen in this light, my case of lector interruptus only makes sense, for what reader, by finishing a novel, would willingly be caught in its sticky web, there to wait in terror until the shadow of the spider looms?

And yet I have read many novels to their conclusion. As have so many. Were we all simply young and naïve, who now, weathered and worn by life, see things more clearly? The theory has its charm, but it fall apart when I admit that my relationship to all those novels over all those years was beset with a curious disability—one that I carefully shielded from view. For the truth is that for many years I have read the endings of novels and then promptly forgotten them. Oh, I’m not saying I can’t tell you about the final lines of Finnegan’s Wake, or In Search of Lost Time—but that is really more a question of responding to flights of rhetoric. I mean the ending in the sense that I think Benjamin is speaking of: the story’s death, a matter not of what is said (because in death of course nothing is said, since it is the end of speech) but in what happens. Thus I draw a blank when I think of the ending of any novel by Dostoyevsky, though I’ve read them all more than once. I’ve at times tried to blame this fault on the endings themselves: not up to his fiction as a whole; or as the result of some terrible very personal failure of intellect. But what if my unconscious simply refuses to store these tokens of death—the endings of novels, that is—in that part of my brain ready to access; what if my unconscious is appalled at the death of the story, of any story, and is in open rebellion against this great fact of the world? Novels like life must come to an end. Life like novels must come to an end. The horror.

•

So there’s this main character in The Interrogation, one Adam Pollo, who has set up housekeeping in an abandoned house on the outskirts of a French coastal city. From the start we are left uncertain (he himself doesn’t know) whether he’s a soldier returning from the war or an escapee from an insane asylum. He has a series of adventures––in some ways the novel is a collection of these adventures. One of them involves a day when he goes to the beach and noticing a stray dog, on an impulse, follows it as it makes its way trotting through the city. It’s not easy following a dog. In fact, it’s very hard work and takes all of Pollo’s attention and skill. The dog stops here and smells this. Trots there and observes that. This might’ve gone on a very long time if the dog hadn’t spotted another dog, an elegant one on a leash, being led by a very proper couple. The dog begins to follow the dog on the leash. So now we’ve gone from a man following a dog to a man following a dog following a dog. The pretty dog on the leash soon turns into a high-end department store, led there by the couple, who is soon followed by the mangy first dog, who is of course followed by the protagonist. The couple descends to the household goods department in a sub basement. While the couple become distracted with their purchases, Adam watches in excruciating embarrassment and fascination as the dog he has been following jumps upon the pampered dog on a leash and starts having sex with it. A series of flashes from a nearby photo booth now bathe the scene in weird electric light. The couple whose dog it is and the other shoppers are completely oblivious to what is happening. The couple having finished their purchases retrieve the leash of their cherished dog now abandoned by her paramour, and with all the dignity in the world leave the department store. End of scene.

J Altern Complement Med 2010;16:753-9.Roodenrys S, Booth levitra side effects D, Bulzomi S, Phipps A, Micallef C, Smoker J. With these rebates under control on levitra discount, a patient can upgrade sexual performances. Use good Moisturizer and sunscreen lotions – viagra sans prescription To protect the device as these are too much expensive and even repairs cost a lot. Throughout twomeyautoworks.com buy tadalafil the day, music from the 50’s era is played here.

•

Benjamin writes: “the novel is significant … not because it presents someone else’s fate to us, perhaps didactically, but because this stranger’s fate by virtue of the flame which consumes it yields us the warmth which we never draw from our own fate.” In the department store scene, Adam, the original man, tries to throw off his (human) fate. Though he comes very close to living the dog’s life, close to Rilke’s notion of “the open,” his tragi-comic failure is to recognize how the animal world is closed to him. He watches the copulating dogs and feels embarrassed; surrounded as he is by the horrific artificial world of buying and selling, he nonetheless cannot throw it off. We warm ourselves on the flame of our fate as we experience the comic realization that Adam Pollo, c’est nous. In the mirrored universe of the novel, we recognize ourselves.

•

But what of the storyteller himself? What role does he play in our drame infime? The storyteller, Benjamin tells us at the end of his essay, “is the figure in which the righteous man encounters himself.” The implication here is the startling one that the writer experiences his own fate in the final pages of a story just as the reader does. If this is so, then he too must feel, at least at the unconscious level, the reader’s latent revulsion against the fate revealed in the ending of the story. (For when the story ends, the writer’s grand illusion—meaning—dies too.) Perhaps we now catch a glimmer of truth emerging through the brume: how in the act of reading/writing, a highly charged, and one might even say erotic, complicity is set up between the reader and writer, as both, united in the text, experience the death of the story—together. Seen in this light, the failure to finish a novel begins to look dramatically different, as does, not incidentally, my failure to finish The Interrogation. For what if it were the case that the reader in declining to finish the novel acts in solidarity with the writer? What if Le Clézio himself, unconsciously at least, never wanted to complete his novel in the first place? What if, in coming face to face with himself through the metaphor of the storyteller, the novelist simultaneously encounters his fate and the entirely natural desire to avoid the cruel and intolerable ordeal unfolded by it? Indeed, the further conclusion now seems unavoidable: any reader who finishes Le Clézio’s wonderful novel inadvertently participates in its destruction, so that like the tapes played at the beginning of the old TV program that burn to a few tendrils of smoke, The Interrogation lives only until the moment we complete it, at which point it self immolates.

•

And so at the end of the journey, and yes, the end of the story, for this, whatever it has been, while laying no claim, is nonetheless a narrative of sorts, my wisdom is limited to the following: by all means I urge you, read the book, but for god’s sake don’t read it from start to finish.

Read More

The virginal heroine of The Portrait of Dor by Osc feeds a group of ducks with pieces of a stick while her friends look on.

I started light—meaning something small and found a volume of just the right heft titled The Bridge over San Lu by Thornton Wild, a story about a group of Mexican peasants who lived on a suspension bridge over a vast jungle paradise. All things considered the reading went well. After that I tried on a more substantial volume, One Flew Over t by Ken Kes, a novel about a heroic nurse who fights off a mad criminal named Murph, who finally attempts to electrocute her. There were other highlights. The Crying of Lot 4 by Thomas Py involved a gang of looney friends who worked at the same post office, and somewhat ominously appears to be the place where the phrase “going postal” was coined. Ulys by James Joy was the toughest read I took on, but it was worth it. Something to do with a girl named Molly whose efforts to find a boyfriend were constantly being thwarted by her grandfather, a dude named Bloom.

Poor order levitra online postural habits are easy to form in this situation. Over production of sex levitra uk browse around this link hormones are also not secreted in sufficient amounts even if endocrine glands are intact. You can without much of a stretch purchase non-specific discount levitra at a modest rate. They can enjoy their love-life by using cheap viagra for women for the treatment of erectile discomfort in men facing depression. But no book at The Library had quite the effect on me as the one I picked up on a fateful evening as the summer wore on. The Portrait of Dor by Osc involved a photograph the narrator had taken of someone, perhaps himself, in flagrante delicto. To make matters worse, somewhere about halfway through, the photo began talking! (I switched to gin thinking the book was probably British.) The virginal love interest of the narrator was terribly distraught over the photograph, which would from time to time appear in ghoulish Halloween garb. The Day of the Dead motif eventually culminated in the setting change to Yucatán peninsula, which by a similar process led to my own switching to mescal as libation of choice, which may have been a mistake. The last pages are a bit of a blur. The collapse of the English class system was followed by a wild foxhunt through the Yucatán prairies. As the tragedy of the plot came to its culminating moments I may have been crying hysterically—drinking mescal is like pouring gasoline on the flames of a lost love, but try it while reading a tragic love story like The Portrait of Dor. I think I was cut off at some point. It’s not entirely clear whether I finished the book and was led to the parking lot or was simply led to the parking lot—I do remember the book being forcibly removed from my hands. And so there I was alone under the sky of South Florida, as alone as the virginal heroine of The Portrait of Dor was under the Mayan sky, though I could only hope the virgin sacrifice planned for her would not also be my fate. I slept in some nearby bushes and woke up with a blinding headache in the wee hours of the morning. I now see why so many people don’t read. Too dangerous.

Read More

It all began three days ago—it seems like eons have passed since—when I woke up with an odd feeling just below my right collarbone. Of course I immediately touched the spot. Nothing strange in that; it’s what we do when something unusual appears on our bodies. What I felt––and it was beyond my field of vision so I could only feel––was a smooth flat nodule that seemed to have formed almost precisely flush with my skin. Naturally I went to the mirror, though at first I didn’t understand what I was looking at. Not that I didn’t know I was looking at my upper torso: there was my chest, my collarbones jutting out a bit too prominently for my taste, and my neck, my gristly neck, of which I’m rather self-conscious. But in addition to these geographically normal items was a black button, uniform, round, and to all appearances made of a durable high quality plastic, situated just below my collarbone.

My first reaction was annoyance. Another normal response. My health is generally good and who wants to deal with a health problem? My second reaction—an impulse, to be precise—was to push the button. I won’t say whether I think this was normal or not, though it’s true, not everyone would have felt this urge. (I had no idea how apt that word would turn out to be.) And yet my desire to push the button could not have felt more completely natural, and I will even venture to say that many would have felt the same way. I almost did push it too, raised my hand until my finger (index) was hovering over the button––when I stopped. Because I suddenly wondered, what if it’s an off button?

Until that instant, the thought had not occurred to me. Not that the button said “Off,” or anything like that. But it’s the nature of a button to turn things on and off. Which raised the further questions, if it was an off button, was it also an on button? And if I did turn it off, would I be in a position to turn it back on? I think you can see the problem, though I must admit the full measure of my difficulties hadn’t hit me. But I did see right away, somewhat bitterly, how much better off I would have been if my first thought had been instead: what if it’s a start button? Perhaps even a kind of physical rejuvenation button. And why isn’t that just as likely? Then I would’ve pushed it immediately in the hopes of being young again, and then whatever would’ve happened would’ve happened. Except, and perhaps you already see the problem, the formula of the question itself more or less demands the negative answer. What if? We aren’t built to ask that question in full-blooded optimism. So in other words, and I saw this pretty quickly, I was being led around by the nose by semantics.

And yet, as I mentioned, I didn’t see the full panoply of the issues right away. In fact I was in a terrible rush, late for work as usual, and because I feared losing my job more than I feared discovering the true purpose of the button I actually managed to push my discovery out of my mind, wash up, dress quickly, and get out the door. And for the most part, that first day was not so terrible. I was quite busy, and though I occasionally felt the button there under my shirt, I taught my classes with good concentration. With the freshman, we read “Ozymandias.” With the juniors, we reviewed vocabulary words. They had trouble with “indulgence.” Only toward the end of the day did I start to wonder if perhaps some of my colleagues or even my students might be experiencing the same health phenomenon, the same kind of button appearing somewhere on their bodies, and I began to wonder if many of us aren’t similarly disabled—though that seems too strong a word—and all undergoing the issue in equal silence.

And then I went home.

That might’ve been a mistake, though how I could have predicted trouble, after my bland first day, I don’t know.

The problem was at home I had nothing to distract me from—the button. I will call it that. My evening, usually dedicated to study (I have been reading the collected works of Georges Sand) quickly devolved into a nightmare, an endless oscillating loop between an increasingly urgent desire to push the button, just push it, just push the god damn button. Push. It. And an equally intense resistance that set itself up as a reverberating clamor in my brain that boomed the words as though from a train-station loudspeaker: what if it’s an off button?

And then I would think, don’t be ridiculous. It could as easily have been a button that did absolutely nothing. Or a button that got rid of my allergies, or my acid reflux, or my toe fungus.

Sleep was out of the question under these circumstances, and the night wore on, and I truly understood the night then, how we are, each of us, lowered in those late hours of dark and silence into its deep well, narrow and cold and dank, where we experience our own hopelessness and taste the awful cold and tainted water of death. I had the TV on, its cool bluish light washing across the room, a movie about some guy in a desert location with motorcycles, and it was then, and only then—I say this with certainty, since it struck me as very odd that it took this long to have such an obvious thought—yet I swear I had not had it until just that moment when I sat on my old easy chair in the den, hopeless in the deep well of night—that I had the thought: who the hell put it there? You see what I mean. Why had it taken this long to have this most obvious of all thoughts? I can’t answer the question. I told myself it had to do with my being one of those people who makes a conscientious effort to be forward-looking. But that sounded like bunkum, and before I could even start to evaluate, I found myself thinking once again, the thought like some invasion of ants crawling up my brainstem, push it, why don’t you just push it? And I could see that another casualty of this medical condition (for so it seemed this was) was that my new obsession made impossible higher order ethical reasoning.

But who did put it there? I quickly ran through the usual suspects that paranoia might suggest: the Obama administration; rogue CIA agents; thugs hired by that

Read More

There’s a scene in Proust that has stayed with me—though I would not perhaps say I’ve been haunted by it; more like, it has lingered on in some cork-lined closet at the back of my head, an on-again, off-again oscillation of long duration. The scene is found in Time Regained, the last volume of In Search of Lost Time, and follows the narrator as he departs from one of the novel’s most famous set pieces: his visit to a brothel in which he discovers Charlus, who broods over In Search of Lost Time the way Satan broods over Paradise Lost, in flagrante delicto.

The narrator walks out into the street from the claustrophobia of the house of prostitution, in which the distorting effects of love and desire have been on display, into the Paris of World War I, as an air raid begins. The streets are suddenly plunged in darkness, antiaircraft guns begin to fire, and it’s even possible, because the narrator is now a few blocks away, that a bomb has fallen on the brothel itself. That bomb, those bombs, falling without warning from the night sky, metaphorically represent love itself, and the entire scene—the plunge into darkness, the sudden appearance of incendiary danger out of the sky, the illumination of the explosions––maps the human experience of desire and love.

The narrator is struck by how little those who are pursuing their pleasures would be distracted by the dangers of falling bombs. “Seldom do we take any note of the social setting or the natural surroundings in which our love affairs are placed. The tempest rages at sea, the ship rolls in every direction, torrents of rain, whipped by the wind, pour down from the sky: we give heed for just an instant––and then only to protect ourselves against some inconvenience it is causing us––to the immense scene in which we and the beloved body we are clasping close are but insignificant atoms.”

It boosts semen load and helps to enjoy intimate moments with their partner, but due to erotic dysfunction of her partner, she always left unsatisfied eroticly which affect them psychologically. purchase viagra uk But experts donssite.com generico levitra on line suggest that men should not feel low since it is a treatable condition and is not unusual. Many chiropractic offices have a massage therapist that can help de stress the body, increase circulation, which then facilitates the movement of oxygen and remove other psychological problems such as stress, confusion, depression, stress and anxiety- Feeling stressed, low and anxious leaves direct impact over the potency acquisition de viagra and desire. Relating to mononuclear viagra online from canada cells, intracerebral, intraspinal and intrathecal administration have worked out.

The metaphor’s power at least partly derives from its fluctuation between its literal and figurative senses. The “immense scene” which forms the backdrop of love is the world and all its immediate dangers. But the “immense scene” is also metaphorically love and desire itself, the dangerous threat that turns the ordered world upside down, erasing external reality the way darkness in a blackout erases the city, and falling upon the unsuspecting flâneur like the explosives pitched from the cockpits of German biplanes. These are literal Gothas dropping bombs on Paris, but they are also representations of the violence and unexpectedness of love which strikes us as though the sky is falling, and meanwhile, we, like blind molds on our urgent business, ignore the very landscape in which we are encased—we, the “insignificant atoms” of the metaphor caught within prodigious geographies of desire.

Proust’s metaphor is like one of those massively complex atoms created in cyclotrons that disintegrates radioactively in milliseconds; in that way, it further reflects the paradox of human passion through the transient glimpse it offers of its ever vanishing essence—an essence that drives and determines us even as we fail to locate it except in the complex and inevitably disintegrating metaphors that artists create in homage to it—and so, yes, perhaps haunted was the right word after all.

Read More