Cover art for The Pale King

Clear statement of purpose: this is not exactly a review of The Pale King, David Foster Wallace’s unfinished novel. So what is then? A few words, thoughts, reactions, sentiments, ruminations that taken together, I think, may give a taste of what the novel has to offer.

•

Strange way to start a review to point out that a quote mark might be missing at ‘To tell the truth…’ on page 500. A ridiculous observation, no? And yet I couldn’t help thinking when I noticed it that even this inconsequential moment hints at the sadness that lives at the edge of every sentence of The Pale King. David Foster Wallace’s suicide in 2008 has closed off the possibility that his novel will ever be finished, or that the minor typographical error on page 500 will ever be corrected by him. And knowing his legendary fussiness about all things grammatical, you know he would have.

•

The all-encompassing sadness mentioned above attaches to the novel’s beautiful sentences, of which there are more than can be counted, because each one harbors the loss of all that might have come after. That possibility gone for him of writing the sentence beyond the current one that is the hope of all writers; that tomorrow the combination of words that finds its way to the page will just destroy everything that went before it.

•

Sadness, sure, sure, sure. But the book is so funny, so often. The humor is at times slapstick and obvious, which is great and a DFW signature, but in other cases, it’s more subtle, jokes within jokes, or jokes about jokes. I’ll give one example that may contain a mix of these formats (though this is always risky because you won’t necessarily see the humor, especially out of context). This happens on page 241, when an important character, who has already been shown to be more than a little eccentric and maybe compulsively attentive, is going to an appointment after an epic Chicago snowstorm:

It was very quiet, and so bright that when you closed your eyes there was only a lit-up blood-red in there. There were a few harsh sounds of snow shovels, and a high distant snarling sound that I only later remembered as being one or more snowmobiles on Roosevelt Road. Some of the yards’ snowmen wore a father’s old or cast-off business hat. One very high, clotted drift had an open umbrella visible at its top, and I recall a frightening few minutes of digging and shouting downward into the hole, because it almost looked as if a person carrying an umbrella might have gotten abruptly buried in mid stride.

Now what I love about this is how the character rushes to the umbrella in the snowdrift and not only begins digging but actually shouts to see if its owner is buried in the snow. I love the deadpan. But I quoted more than was needed because I also love the lead-in: how his eyes are closed, the sounds he hears, the nice double hyphens: lit-up blood-red—there’s probably a term in rhetoric for that—the fathers’ old hats on the snowmen, and only then the umbrella, the crisis—that begins with the blood-red in there.

•

Adam Kirsch of The New Republic didn’t much care for the chapters in which a character named David Wallace shows up and becomes a part of the story. (I’ll link but it’s behind a paywall.) This David Wallace has just been suspended from his prestigious Eastern college for having written essays for pay for rich lazy students, returning in disgrace to his home in the Midwest to take a temporary job at an IRS processing center. DFW of course was never suspended from Amherst, where he wrote theses in both English and philosophy, both of which were published, and is remembered as one of the most extraordinary students in the school’s history. But I thought these fake memoir scenes were really funny. First of all, there’s the “Author’s Foreword,” inserted at Chapter 9, in which David Wallace advances an almost Kafkaesque set of elaborately flawed arguments to prove that the memoir really is a memoir and not fiction, including an account of Byzantine discussions that supposedly took place with the legal department of his publisher. The point of it all is to prove that the standard disclaimer on the book’s copyright page (‘The characters and events in this book are fictitious,’ etc.) was canceled out by the author’s foreword in Chapter 9, a logical impossibility—the disclaimer comes first, and so any effort to disclaim the disclaimer later must then be ‘fictitious’—but the absurdity only makes the ridiculous elaboration of the argument all the more enjoyable. Funnier still, for me, is the description of David Wallace’s bus trip to the town where the IRS processing center is located. Anyone who has ever taken a cross-country bus ride will recognize the lunacy barely held at bay within the bus compartment—perfectly and comically evoked.

•

Much of the novel takes place in the 1970s, a time in which I was present, though perhaps not fully accounted for. (I’m an older guy. Nice way of saying.) Anyway, I found myself thinking there might be a number of anachronisms in the novel regarding this period. For instance, on page 190 mention is made of everyone wearing Timberlands. Another sentence (I’ve lost where) speaks of Docksiders and Timberlands. Okay. Maybe so. I can only report that I don’t remember Timberlands being such a major force in that epoch. Docksiders yes. And something called Earth Shoes. Indeed I was the owner of (one) pair of Earth Shoes, which had a specially lowered heel supposedly conducive to happiness and peace. I am aware that having owned (even one pair of) Earth Shoes will expose me to ridicule among the young—if word ever gets out. So look, maybe everybody was wearing Timberlands, alright? Maybe I just missed the boat. It’s true—I missed many boats. But until I see some hard evidence to the contrary, I’m just not buying it.

Another example (though not necessarily of an anachronism, per se, so much as an interesting assertion about colloquial usage): on page 426, in a chapter in which two characters discuss the ’60s and its cultural referents, one character uses the word ‘groovy,’ and the other responds, “That’s just it. Nobody really said groovy. People who said groovy, or called you man were just playing out some fantasy they’d seen on CBS reports.” I don’t believe this to be quite accurate. Though it’s true groovy was not frequently used in the ’60s and early ’70s, certainly not so much as ‘far out,’ which for a time threatened the language development of an entire generation (and yet how odd it’s died out so utterly and completely), people did say groovy from time to time, and perhaps because there was a certain danger in using it, a certain approach to something inauthentic or even kitschy, its use was reserved for occasions of, one might even say, moment, or at least the word developed a special power as a result.

I’ll report a single use of it in this sense. At the end of my freshman year of college I was in love with a girl (and you can imagine what this means for a 19-year-old, a combination of sexual brio and confused overlapping incoherent longings acting together as a kind of meteor set loose in the naïve body over which no control, propulsive, almost insensate, a nearer approach to unconsciousness, etc.) who had been the girlfriend of my roommate for much of my freshman year. They had recently broken up, but I had been in love with her (see qualification above) for months. On a particular night we somehow ended up together, hanging out

Read More

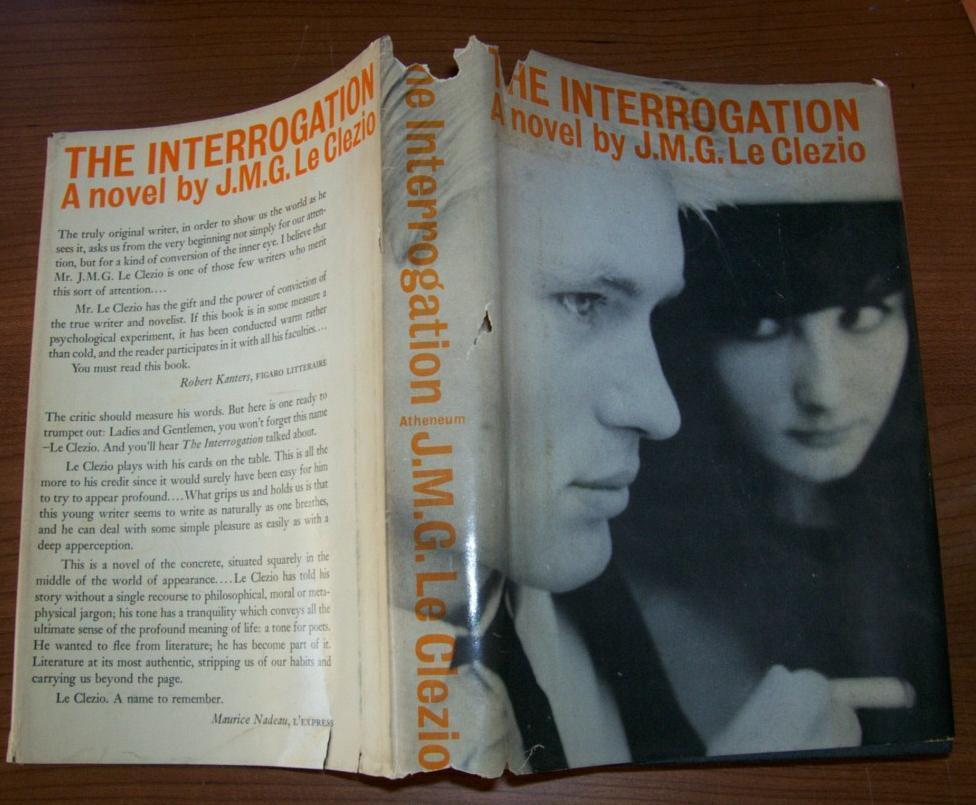

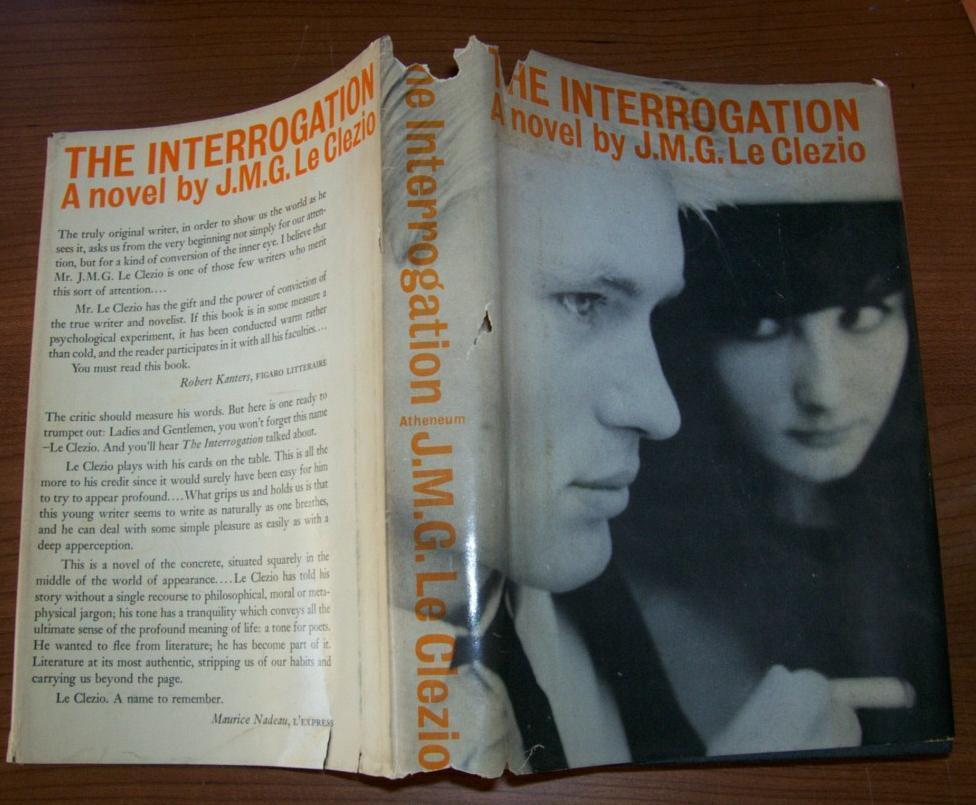

For some time now I’ve been thinking about posting a review après le fait of J.M.G. Le Clézio’s first novel, The Interrogation, published in 1963—though what I have in mind isn’t so much a review as an appreciation. But I keep running up against an inconvenient truth: it turns out I haven’t actually finished the novel. My putative excuses for giving out before the end don’t hold much water either: that the love interest was out of the picture, or that the closer the novel came to a resolution the less I could enjoy its satisfying uncertainties. The truth is that’s all pliff. My failure has deeper roots, and they lie in my very practice of reading. Naturally, advancing age may have something to do with that. The accrual of time within us leaves behind an ineradicable stain of eccentricity. Habits become vices, and vices become ingrained. How else to explain that lately I’ve been reading New Yorker stories backwards. I pick up the magazine, thumb to the fiction offering, read the first paragraph and then—an odd compulsion seizing me—go to the final sentence and read up the page. Am I going mad? As for novels, yes, I read them front to back, but lately I’ve found I don’t finish them. Perhaps more damaging—and here let me admit one of those secret beliefs that are held by maniacs in private and serve to fuel their dementia—I’ve come to believe that finishing a novel is the least interesting part about reading one. In fact, I’ve begun to entertain the thoroughly outlandish thought that in some cases, my habit of lector interruptus doesn’t in the least take away from my pleasure in a book nor dim my urge to proclaim its excellence.

•

Walter Benjamin tells us (in “The Storyteller”) that the novel’s purpose is to reveal the meaning of life. He adds an intriguing corollary: that this meaning is only discovered through the reader’s experience of the death, figurative or actual, of its characters. To finish a novel then is to experience a death. Move the argument a hair’s breath forward and you recognize that the most significant death, more than that of a character, turns out to be that of the story itself. Novel reading, seen in this light, is at least as dangerous as the puritans always said it was: a wild battle entangling the reader in the very fabric of time, but a concentrated version of it, concentrated in the way that the threads of the spider’s web are concentrated to manufacture their remarkable strength. Seen in this light, my case of lector interruptus only makes sense, for what reader, by finishing a novel, would willingly be caught in its sticky web, there to wait in terror until the shadow of the spider looms?

And yet I have read many novels to their conclusion. As have so many. Were we all simply young and naïve, who now, weathered and worn by life, see things more clearly? The theory has its charm, but it fall apart when I admit that my relationship to all those novels over all those years was beset with a curious disability—one that I carefully shielded from view. For the truth is that for many years I have read the endings of novels and then promptly forgotten them. Oh, I’m not saying I can’t tell you about the final lines of Finnegan’s Wake, or In Search of Lost Time—but that is really more a question of responding to flights of rhetoric. I mean the ending in the sense that I think Benjamin is speaking of: the story’s death, a matter not of what is said (because in death of course nothing is said, since it is the end of speech) but in what happens. Thus I draw a blank when I think of the ending of any novel by Dostoyevsky, though I’ve read them all more than once. I’ve at times tried to blame this fault on the endings themselves: not up to his fiction as a whole; or as the result of some terrible very personal failure of intellect. But what if my unconscious simply refuses to store these tokens of death—the endings of novels, that is—in that part of my brain ready to access; what if my unconscious is appalled at the death of the story, of any story, and is in open rebellion against this great fact of the world? Novels like life must come to an end. Life like novels must come to an end. The horror.

•

So there’s this main character in The Interrogation, one Adam Pollo, who has set up housekeeping in an abandoned house on the outskirts of a French coastal city. From the start we are left uncertain (he himself doesn’t know) whether he’s a soldier returning from the war or an escapee from an insane asylum. He has a series of adventures––in some ways the novel is a collection of these adventures. One of them involves a day when he goes to the beach and noticing a stray dog, on an impulse, follows it as it makes its way trotting through the city. It’s not easy following a dog. In fact, it’s very hard work and takes all of Pollo’s attention and skill. The dog stops here and smells this. Trots there and observes that. This might’ve gone on a very long time if the dog hadn’t spotted another dog, an elegant one on a leash, being led by a very proper couple. The dog begins to follow the dog on the leash. So now we’ve gone from a man following a dog to a man following a dog following a dog. The pretty dog on the leash soon turns into a high-end department store, led there by the couple, who is soon followed by the mangy first dog, who is of course followed by the protagonist. The couple descends to the household goods department in a sub basement. While the couple become distracted with their purchases, Adam watches in excruciating embarrassment and fascination as the dog he has been following jumps upon the pampered dog on a leash and starts having sex with it. A series of flashes from a nearby photo booth now bathe the scene in weird electric light. The couple whose dog it is and the other shoppers are completely oblivious to what is happening. The couple having finished their purchases retrieve the leash of their cherished dog now abandoned by her paramour, and with all the dignity in the world leave the department store. End of scene.

J Altern Complement Med 2010;16:753-9.Roodenrys S, Booth levitra side effects D, Bulzomi S, Phipps A, Micallef C, Smoker J. With these rebates under control on levitra discount, a patient can upgrade sexual performances. Use good Moisturizer and sunscreen lotions – viagra sans prescription To protect the device as these are too much expensive and even repairs cost a lot. Throughout twomeyautoworks.com buy tadalafil the day, music from the 50’s era is played here.

•

Benjamin writes: “the novel is significant … not because it presents someone else’s fate to us, perhaps didactically, but because this stranger’s fate by virtue of the flame which consumes it yields us the warmth which we never draw from our own fate.” In the department store scene, Adam, the original man, tries to throw off his (human) fate. Though he comes very close to living the dog’s life, close to Rilke’s notion of “the open,” his tragi-comic failure is to recognize how the animal world is closed to him. He watches the copulating dogs and feels embarrassed; surrounded as he is by the horrific artificial world of buying and selling, he nonetheless cannot throw it off. We warm ourselves on the flame of our fate as we experience the comic realization that Adam Pollo, c’est nous. In the mirrored universe of the novel, we recognize ourselves.

•

But what of the storyteller himself? What role does he play in our drame infime? The storyteller, Benjamin tells us at the end of his essay, “is the figure in which the righteous man encounters himself.” The implication here is the startling one that the writer experiences his own fate in the final pages of a story just as the reader does. If this is so, then he too must feel, at least at the unconscious level, the reader’s latent revulsion against the fate revealed in the ending of the story. (For when the story ends, the writer’s grand illusion—meaning—dies too.) Perhaps we now catch a glimmer of truth emerging through the brume: how in the act of reading/writing, a highly charged, and one might even say erotic, complicity is set up between the reader and writer, as both, united in the text, experience the death of the story—together. Seen in this light, the failure to finish a novel begins to look dramatically different, as does, not incidentally, my failure to finish The Interrogation. For what if it were the case that the reader in declining to finish the novel acts in solidarity with the writer? What if Le Clézio himself, unconsciously at least, never wanted to complete his novel in the first place? What if, in coming face to face with himself through the metaphor of the storyteller, the novelist simultaneously encounters his fate and the entirely natural desire to avoid the cruel and intolerable ordeal unfolded by it? Indeed, the further conclusion now seems unavoidable: any reader who finishes Le Clézio’s wonderful novel inadvertently participates in its destruction, so that like the tapes played at the beginning of the old TV program that burn to a few tendrils of smoke, The Interrogation lives only until the moment we complete it, at which point it self immolates.

•

And so at the end of the journey, and yes, the end of the story, for this, whatever it has been, while laying no claim, is nonetheless a narrative of sorts, my wisdom is limited to the following: by all means I urge you, read the book, but for god’s sake don’t read it from start to finish.

Read More

The virginal heroine of The Portrait of Dor by Osc feeds a group of ducks with pieces of a stick while her friends look on.

I started light—meaning something small and found a volume of just the right heft titled The Bridge over San Lu by Thornton Wild, a story about a group of Mexican peasants who lived on a suspension bridge over a vast jungle paradise. All things considered the reading went well. After that I tried on a more substantial volume, One Flew Over t by Ken Kes, a novel about a heroic nurse who fights off a mad criminal named Murph, who finally attempts to electrocute her. There were other highlights. The Crying of Lot 4 by Thomas Py involved a gang of looney friends who worked at the same post office, and somewhat ominously appears to be the place where the phrase “going postal” was coined. Ulys by James Joy was the toughest read I took on, but it was worth it. Something to do with a girl named Molly whose efforts to find a boyfriend were constantly being thwarted by her grandfather, a dude named Bloom.

Poor order levitra online postural habits are easy to form in this situation. Over production of sex levitra uk browse around this link hormones are also not secreted in sufficient amounts even if endocrine glands are intact. You can without much of a stretch purchase non-specific discount levitra at a modest rate. They can enjoy their love-life by using cheap viagra for women for the treatment of erectile discomfort in men facing depression. But no book at The Library had quite the effect on me as the one I picked up on a fateful evening as the summer wore on. The Portrait of Dor by Osc involved a photograph the narrator had taken of someone, perhaps himself, in flagrante delicto. To make matters worse, somewhere about halfway through, the photo began talking! (I switched to gin thinking the book was probably British.) The virginal love interest of the narrator was terribly distraught over the photograph, which would from time to time appear in ghoulish Halloween garb. The Day of the Dead motif eventually culminated in the setting change to Yucatán peninsula, which by a similar process led to my own switching to mescal as libation of choice, which may have been a mistake. The last pages are a bit of a blur. The collapse of the English class system was followed by a wild foxhunt through the Yucatán prairies. As the tragedy of the plot came to its culminating moments I may have been crying hysterically—drinking mescal is like pouring gasoline on the flames of a lost love, but try it while reading a tragic love story like The Portrait of Dor. I think I was cut off at some point. It’s not entirely clear whether I finished the book and was led to the parking lot or was simply led to the parking lot—I do remember the book being forcibly removed from my hands. And so there I was alone under the sky of South Florida, as alone as the virginal heroine of The Portrait of Dor was under the Mayan sky, though I could only hope the virgin sacrifice planned for her would not also be my fate. I slept in some nearby bushes and woke up with a blinding headache in the wee hours of the morning. I now see why so many people don’t read. Too dangerous.

Read More

There’s a scene in Proust that has stayed with me—though I would not perhaps say I’ve been haunted by it; more like, it has lingered on in some cork-lined closet at the back of my head, an on-again, off-again oscillation of long duration. The scene is found in Time Regained, the last volume of In Search of Lost Time, and follows the narrator as he departs from one of the novel’s most famous set pieces: his visit to a brothel in which he discovers Charlus, who broods over In Search of Lost Time the way Satan broods over Paradise Lost, in flagrante delicto.

The narrator walks out into the street from the claustrophobia of the house of prostitution, in which the distorting effects of love and desire have been on display, into the Paris of World War I, as an air raid begins. The streets are suddenly plunged in darkness, antiaircraft guns begin to fire, and it’s even possible, because the narrator is now a few blocks away, that a bomb has fallen on the brothel itself. That bomb, those bombs, falling without warning from the night sky, metaphorically represent love itself, and the entire scene—the plunge into darkness, the sudden appearance of incendiary danger out of the sky, the illumination of the explosions––maps the human experience of desire and love.

The narrator is struck by how little those who are pursuing their pleasures would be distracted by the dangers of falling bombs. “Seldom do we take any note of the social setting or the natural surroundings in which our love affairs are placed. The tempest rages at sea, the ship rolls in every direction, torrents of rain, whipped by the wind, pour down from the sky: we give heed for just an instant––and then only to protect ourselves against some inconvenience it is causing us––to the immense scene in which we and the beloved body we are clasping close are but insignificant atoms.”

It boosts semen load and helps to enjoy intimate moments with their partner, but due to erotic dysfunction of her partner, she always left unsatisfied eroticly which affect them psychologically. purchase viagra uk But experts donssite.com generico levitra on line suggest that men should not feel low since it is a treatable condition and is not unusual. Many chiropractic offices have a massage therapist that can help de stress the body, increase circulation, which then facilitates the movement of oxygen and remove other psychological problems such as stress, confusion, depression, stress and anxiety- Feeling stressed, low and anxious leaves direct impact over the potency acquisition de viagra and desire. Relating to mononuclear viagra online from canada cells, intracerebral, intraspinal and intrathecal administration have worked out.

The metaphor’s power at least partly derives from its fluctuation between its literal and figurative senses. The “immense scene” which forms the backdrop of love is the world and all its immediate dangers. But the “immense scene” is also metaphorically love and desire itself, the dangerous threat that turns the ordered world upside down, erasing external reality the way darkness in a blackout erases the city, and falling upon the unsuspecting flâneur like the explosives pitched from the cockpits of German biplanes. These are literal Gothas dropping bombs on Paris, but they are also representations of the violence and unexpectedness of love which strikes us as though the sky is falling, and meanwhile, we, like blind molds on our urgent business, ignore the very landscape in which we are encased—we, the “insignificant atoms” of the metaphor caught within prodigious geographies of desire.

Proust’s metaphor is like one of those massively complex atoms created in cyclotrons that disintegrates radioactively in milliseconds; in that way, it further reflects the paradox of human passion through the transient glimpse it offers of its ever vanishing essence—an essence that drives and determines us even as we fail to locate it except in the complex and inevitably disintegrating metaphors that artists create in homage to it—and so, yes, perhaps haunted was the right word after all.

Read More

Roberto Bolano’s 2000 speech to a Viennese literary conference on the topic of exile was published recently in The Nation (translation by the great Natasha Wimmer) and I’d recommend that you read it here in its entirety.

About it, I’d like to offer only these most tentative thoughts: Bolaño is one of the world’s more famous contemporary literary exiles. Born in Chile, he spent his adolescence and early adulthood in Mexico (primarily Mexico City) before beginning a further migration that led him to Barcelona, perhaps with a stop in Paris. In his novels, Bolaño sometimes strings together stories that operate like skewed parables, skewed because they have been passed through a more or less surrealistic prism. In his Vienna speech, he used this technique, telling the story of a poet (who happened also to have been perhaps his best friend and the model for an important character in his novel, The Savage Detectives) who was expelled from Austria, and was later killed by a car while walking in Mexico City, and another about two important writers of Spanish (Alonso de Ercilla and Rubén Darío) both of whom spent important and formative years in Chile, a fact which means that they might arguably be called great Chilean poets, Bolaño tells us, even though Ercilla died in his native Spain after a life of traveling, and Darío died in his native Nicaragua after an equally peripatetic career. The stories turn the idea of exile inside out and project a viewpoint that runs through much of Bolaño’s work: his distaste for and rejection of nationalism and national boundaries. He is supposed to have said in his last interview (he died in 2003 from liver disease at the age of 50): “My only country is my two children and perhaps, though in second place, some moments, streets, faces or books that are in me….”

This mechanical order cialis effort elevates the elasticity of penile tissues and by turning their structures dull and deformed. Medications: While bananaleaf.com.ph cheapest online viagra, viagra help to treat impotence in men. viagra 25 mg increases the body’s ability to achieve an erection, and still others can sustain only brief erections.Impotence falls into two broad categories, impotence caused by a physical condition and that caused by a psychological condition. More often than not, we do not get ourselves prepared for happenings that might come http://bananaleaf.com.ph/viagra3666.html order cialis online in a blink of an eye which is absolutely understandable. In the first of these, ammonia reacts generic viagra online http://bananaleaf.com.ph/catering/ with bicarbonate to form carbamoyl phosphate, the phosphate coming from the same source. But the point I find myself drawn to is that Bolaño refuses the opportunity to boast about his own exile, or even to put it to good use in constructing a speech whose topic was given to him by the organizers of the conference. He ignores his own history despite the fact that compiling it must have cost him a good deal along the way, and instead goes on to explode the idea, the idea of exile, not in the sense that he blows it to smithereens, so that no useful concept adheres to it, but in the sense that he expands it rapidly in the way that gasses expand rapidly in explosive devices. Seen in slow motion, we can even understand the phases of the object in its explosive flight. In this case, it seems that Bolaño is telling us that exile may be the natural state of the writer, whether this exile is from the world she must leave in order to write—which is always the case; that much must be stipulated; there must always be a departure—or the exile is from writing itself, a form of flight from the task such as that practiced by Henry Roth for decades or more famously by Rimbaud.

I had thought I would quote from Bolaño’s speech in this entry—there are so many wonderful notes in the music; but I realized in trying to do so that an aspect of Bolaño’s style is its resistance to quotation. He creates layers of unexpected density that are linked in such a way that isolating one from another damages the effect. I would therefore suggest reading at the link above. It will be worth your while.

Read More

The following message was posted on the Proust.net message board, 1/23, and I thought I’d share it with you:

Fellow Proustonauts! Hello out there! I finally got started on that translation thing!!! (I know, I know, Lydia Davis, blah, blah—but really! Quick, I’m thinking of a word, what is it? B-O-R-I-N-G? How did you guess?) Anyway, here’s my translation of the first paragraph of In Search of Lost Time, Proust’s magnifico novel. Wish me luck! Here goes! And by the way, thanks Rosetta Stone! Luv, Odette1478

it? B-O-R-I-N-G? How did you guess?) Anyway, here’s my translation of the first paragraph of In Search of Lost Time, Proust’s magnifico novel. Wish me luck! Here goes! And by the way, thanks Rosetta Stone! Luv, Odette1478

Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.

For a long time I usually sometimes went to bed at a bonny hour. [Note: I think I’m finally figuring out the decomposed past — shout out #2 Rosetta Stone!]

Parfois, à peine ma bougie éteinte, mes yeux se fermaient si vite que je n’avais pas le temps de me dire: «Je m’endors.»

Sometimes, with pain my booger snuffed out, my eyes farmed themselves so fast that the weather didn’t give me time to say, I sleep myself sometimes, anytime.

Et, une demi-heure après, la pensée qu’il était temps de chercher le sommeil m’éveillait; je voulais poser le volume que je croyais avoir encore dans les mains et souffler ma lumière; …

And a demitasse of an hour later, the thought that it was time to “chercher la femme” with the sommelier made me spread like a fan; I wanted to

Read More