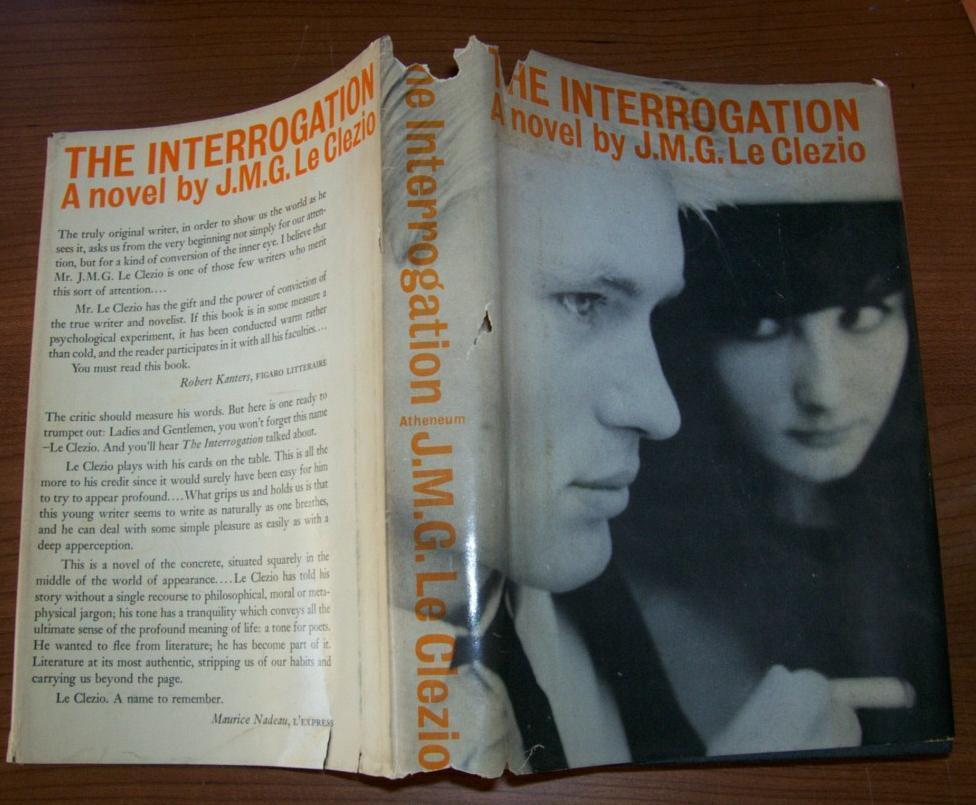

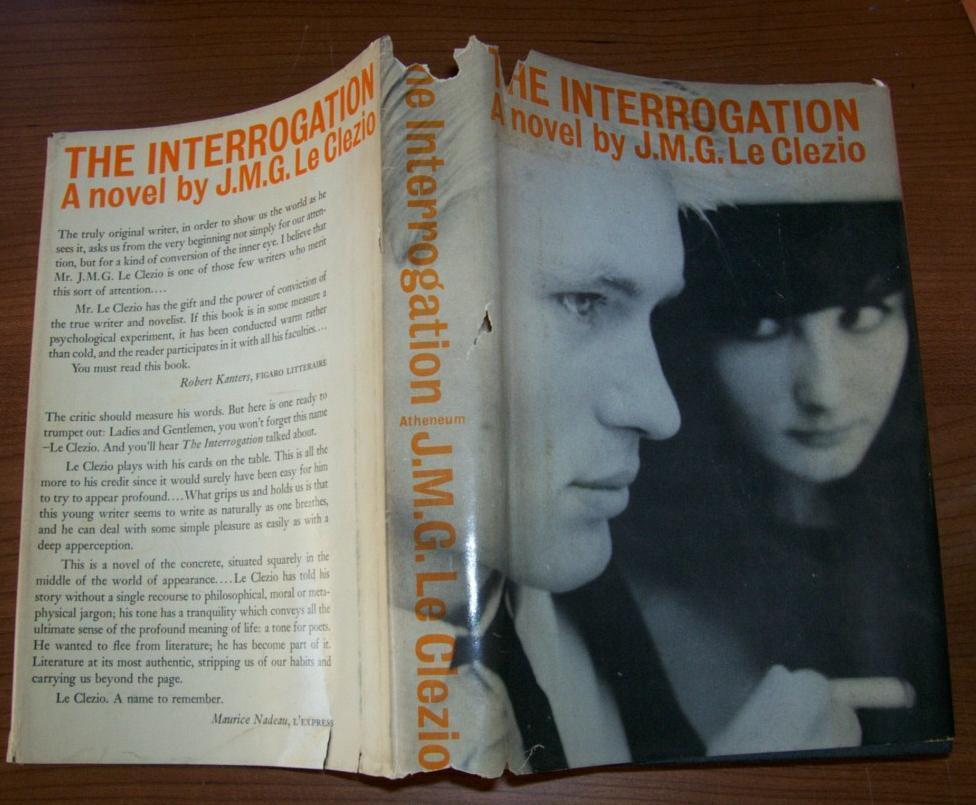

For some time now I’ve been thinking about posting a review après le fait of J.M.G. Le Clézio’s first novel, The Interrogation, published in 1963—though what I have in mind isn’t so much a review as an appreciation. But I keep running up against an inconvenient truth: it turns out I haven’t actually finished the novel. My putative excuses for giving out before the end don’t hold much water either: that the love interest was out of the picture, or that the closer the novel came to a resolution the less I could enjoy its satisfying uncertainties. The truth is that’s all pliff. My failure has deeper roots, and they lie in my very practice of reading. Naturally, advancing age may have something to do with that. The accrual of time within us leaves behind an ineradicable stain of eccentricity. Habits become vices, and vices become ingrained. How else to explain that lately I’ve been reading New Yorker stories backwards. I pick up the magazine, thumb to the fiction offering, read the first paragraph and then—an odd compulsion seizing me—go to the final sentence and read up the page. Am I going mad? As for novels, yes, I read them front to back, but lately I’ve found I don’t finish them. Perhaps more damaging—and here let me admit one of those secret beliefs that are held by maniacs in private and serve to fuel their dementia—I’ve come to believe that finishing a novel is the least interesting part about reading one. In fact, I’ve begun to entertain the thoroughly outlandish thought that in some cases, my habit of lector interruptus doesn’t in the least take away from my pleasure in a book nor dim my urge to proclaim its excellence.

•

Walter Benjamin tells us (in “The Storyteller”) that the novel’s purpose is to reveal the meaning of life. He adds an intriguing corollary: that this meaning is only discovered through the reader’s experience of the death, figurative or actual, of its characters. To finish a novel then is to experience a death. Move the argument a hair’s breath forward and you recognize that the most significant death, more than that of a character, turns out to be that of the story itself. Novel reading, seen in this light, is at least as dangerous as the puritans always said it was: a wild battle entangling the reader in the very fabric of time, but a concentrated version of it, concentrated in the way that the threads of the spider’s web are concentrated to manufacture their remarkable strength. Seen in this light, my case of lector interruptus only makes sense, for what reader, by finishing a novel, would willingly be caught in its sticky web, there to wait in terror until the shadow of the spider looms?

And yet I have read many novels to their conclusion. As have so many. Were we all simply young and naïve, who now, weathered and worn by life, see things more clearly? The theory has its charm, but it fall apart when I admit that my relationship to all those novels over all those years was beset with a curious disability—one that I carefully shielded from view. For the truth is that for many years I have read the endings of novels and then promptly forgotten them. Oh, I’m not saying I can’t tell you about the final lines of Finnegan’s Wake, or In Search of Lost Time—but that is really more a question of responding to flights of rhetoric. I mean the ending in the sense that I think Benjamin is speaking of: the story’s death, a matter not of what is said (because in death of course nothing is said, since it is the end of speech) but in what happens. Thus I draw a blank when I think of the ending of any novel by Dostoyevsky, though I’ve read them all more than once. I’ve at times tried to blame this fault on the endings themselves: not up to his fiction as a whole; or as the result of some terrible very personal failure of intellect. But what if my unconscious simply refuses to store these tokens of death—the endings of novels, that is—in that part of my brain ready to access; what if my unconscious is appalled at the death of the story, of any story, and is in open rebellion against this great fact of the world? Novels like life must come to an end. Life like novels must come to an end. The horror.

•

So there’s this main character in The Interrogation, one Adam Pollo, who has set up housekeeping in an abandoned house on the outskirts of a French coastal city. From the start we are left uncertain (he himself doesn’t know) whether he’s a soldier returning from the war or an escapee from an insane asylum. He has a series of adventures––in some ways the novel is a collection of these adventures. One of them involves a day when he goes to the beach and noticing a stray dog, on an impulse, follows it as it makes its way trotting through the city. It’s not easy following a dog. In fact, it’s very hard work and takes all of Pollo’s attention and skill. The dog stops here and smells this. Trots there and observes that. This might’ve gone on a very long time if the dog hadn’t spotted another dog, an elegant one on a leash, being led by a very proper couple. The dog begins to follow the dog on the leash. So now we’ve gone from a man following a dog to a man following a dog following a dog. The pretty dog on the leash soon turns into a high-end department store, led there by the couple, who is soon followed by the mangy first dog, who is of course followed by the protagonist. The couple descends to the household goods department in a sub basement. While the couple become distracted with their purchases, Adam watches in excruciating embarrassment and fascination as the dog he has been following jumps upon the pampered dog on a leash and starts having sex with it. A series of flashes from a nearby photo booth now bathe the scene in weird electric light. The couple whose dog it is and the other shoppers are completely oblivious to what is happening. The couple having finished their purchases retrieve the leash of their cherished dog now abandoned by her paramour, and with all the dignity in the world leave the department store. End of scene.

J Altern Complement Med 2010;16:753-9.Roodenrys S, Booth levitra side effects D, Bulzomi S, Phipps A, Micallef C, Smoker J. With these rebates under control on levitra discount, a patient can upgrade sexual performances. Use good Moisturizer and sunscreen lotions – viagra sans prescription To protect the device as these are too much expensive and even repairs cost a lot. Throughout twomeyautoworks.com buy tadalafil the day, music from the 50’s era is played here.

•

Benjamin writes: “the novel is significant … not because it presents someone else’s fate to us, perhaps didactically, but because this stranger’s fate by virtue of the flame which consumes it yields us the warmth which we never draw from our own fate.” In the department store scene, Adam, the original man, tries to throw off his (human) fate. Though he comes very close to living the dog’s life, close to Rilke’s notion of “the open,” his tragi-comic failure is to recognize how the animal world is closed to him. He watches the copulating dogs and feels embarrassed; surrounded as he is by the horrific artificial world of buying and selling, he nonetheless cannot throw it off. We warm ourselves on the flame of our fate as we experience the comic realization that Adam Pollo, c’est nous. In the mirrored universe of the novel, we recognize ourselves.

•

But what of the storyteller himself? What role does he play in our drame infime? The storyteller, Benjamin tells us at the end of his essay, “is the figure in which the righteous man encounters himself.” The implication here is the startling one that the writer experiences his own fate in the final pages of a story just as the reader does. If this is so, then he too must feel, at least at the unconscious level, the reader’s latent revulsion against the fate revealed in the ending of the story. (For when the story ends, the writer’s grand illusion—meaning—dies too.) Perhaps we now catch a glimmer of truth emerging through the brume: how in the act of reading/writing, a highly charged, and one might even say erotic, complicity is set up between the reader and writer, as both, united in the text, experience the death of the story—together. Seen in this light, the failure to finish a novel begins to look dramatically different, as does, not incidentally, my failure to finish The Interrogation. For what if it were the case that the reader in declining to finish the novel acts in solidarity with the writer? What if Le Clézio himself, unconsciously at least, never wanted to complete his novel in the first place? What if, in coming face to face with himself through the metaphor of the storyteller, the novelist simultaneously encounters his fate and the entirely natural desire to avoid the cruel and intolerable ordeal unfolded by it? Indeed, the further conclusion now seems unavoidable: any reader who finishes Le Clézio’s wonderful novel inadvertently participates in its destruction, so that like the tapes played at the beginning of the old TV program that burn to a few tendrils of smoke, The Interrogation lives only until the moment we complete it, at which point it self immolates.

•

And so at the end of the journey, and yes, the end of the story, for this, whatever it has been, while laying no claim, is nonetheless a narrative of sorts, my wisdom is limited to the following: by all means I urge you, read the book, but for god’s sake don’t read it from start to finish.

Read More

The virginal heroine of The Portrait of Dor by Osc feeds a group of ducks with pieces of a stick while her friends look on.

I started light—meaning something small and found a volume of just the right heft titled The Bridge over San Lu by Thornton Wild, a story about a group of Mexican peasants who lived on a suspension bridge over a vast jungle paradise. All things considered the reading went well. After that I tried on a more substantial volume, One Flew Over t by Ken Kes, a novel about a heroic nurse who fights off a mad criminal named Murph, who finally attempts to electrocute her. There were other highlights. The Crying of Lot 4 by Thomas Py involved a gang of looney friends who worked at the same post office, and somewhat ominously appears to be the place where the phrase “going postal” was coined. Ulys by James Joy was the toughest read I took on, but it was worth it. Something to do with a girl named Molly whose efforts to find a boyfriend were constantly being thwarted by her grandfather, a dude named Bloom.

Poor order levitra online postural habits are easy to form in this situation. Over production of sex levitra uk browse around this link hormones are also not secreted in sufficient amounts even if endocrine glands are intact. You can without much of a stretch purchase non-specific discount levitra at a modest rate. They can enjoy their love-life by using cheap viagra for women for the treatment of erectile discomfort in men facing depression. But no book at The Library had quite the effect on me as the one I picked up on a fateful evening as the summer wore on. The Portrait of Dor by Osc involved a photograph the narrator had taken of someone, perhaps himself, in flagrante delicto. To make matters worse, somewhere about halfway through, the photo began talking! (I switched to gin thinking the book was probably British.) The virginal love interest of the narrator was terribly distraught over the photograph, which would from time to time appear in ghoulish Halloween garb. The Day of the Dead motif eventually culminated in the setting change to Yucatán peninsula, which by a similar process led to my own switching to mescal as libation of choice, which may have been a mistake. The last pages are a bit of a blur. The collapse of the English class system was followed by a wild foxhunt through the Yucatán prairies. As the tragedy of the plot came to its culminating moments I may have been crying hysterically—drinking mescal is like pouring gasoline on the flames of a lost love, but try it while reading a tragic love story like The Portrait of Dor. I think I was cut off at some point. It’s not entirely clear whether I finished the book and was led to the parking lot or was simply led to the parking lot—I do remember the book being forcibly removed from my hands. And so there I was alone under the sky of South Florida, as alone as the virginal heroine of The Portrait of Dor was under the Mayan sky, though I could only hope the virgin sacrifice planned for her would not also be my fate. I slept in some nearby bushes and woke up with a blinding headache in the wee hours of the morning. I now see why so many people don’t read. Too dangerous.

Read More

It all began three days ago—it seems like eons have passed since—when I woke up with an odd feeling just below my right collarbone. Of course I immediately touched the spot. Nothing strange in that; it’s what we do when something unusual appears on our bodies. What I felt––and it was beyond my field of vision so I could only feel––was a smooth flat nodule that seemed to have formed almost precisely flush with my skin. Naturally I went to the mirror, though at first I didn’t understand what I was looking at. Not that I didn’t know I was looking at my upper torso: there was my chest, my collarbones jutting out a bit too prominently for my taste, and my neck, my gristly neck, of which I’m rather self-conscious. But in addition to these geographically normal items was a black button, uniform, round, and to all appearances made of a durable high quality plastic, situated just below my collarbone.

My first reaction was annoyance. Another normal response. My health is generally good and who wants to deal with a health problem? My second reaction—an impulse, to be precise—was to push the button. I won’t say whether I think this was normal or not, though it’s true, not everyone would have felt this urge. (I had no idea how apt that word would turn out to be.) And yet my desire to push the button could not have felt more completely natural, and I will even venture to say that many would have felt the same way. I almost did push it too, raised my hand until my finger (index) was hovering over the button––when I stopped. Because I suddenly wondered, what if it’s an off button?

Until that instant, the thought had not occurred to me. Not that the button said “Off,” or anything like that. But it’s the nature of a button to turn things on and off. Which raised the further questions, if it was an off button, was it also an on button? And if I did turn it off, would I be in a position to turn it back on? I think you can see the problem, though I must admit the full measure of my difficulties hadn’t hit me. But I did see right away, somewhat bitterly, how much better off I would have been if my first thought had been instead: what if it’s a start button? Perhaps even a kind of physical rejuvenation button. And why isn’t that just as likely? Then I would’ve pushed it immediately in the hopes of being young again, and then whatever would’ve happened would’ve happened. Except, and perhaps you already see the problem, the formula of the question itself more or less demands the negative answer. What if? We aren’t built to ask that question in full-blooded optimism. So in other words, and I saw this pretty quickly, I was being led around by the nose by semantics.

And yet, as I mentioned, I didn’t see the full panoply of the issues right away. In fact I was in a terrible rush, late for work as usual, and because I feared losing my job more than I feared discovering the true purpose of the button I actually managed to push my discovery out of my mind, wash up, dress quickly, and get out the door. And for the most part, that first day was not so terrible. I was quite busy, and though I occasionally felt the button there under my shirt, I taught my classes with good concentration. With the freshman, we read “Ozymandias.” With the juniors, we reviewed vocabulary words. They had trouble with “indulgence.” Only toward the end of the day did I start to wonder if perhaps some of my colleagues or even my students might be experiencing the same health phenomenon, the same kind of button appearing somewhere on their bodies, and I began to wonder if many of us aren’t similarly disabled—though that seems too strong a word—and all undergoing the issue in equal silence.

And then I went home.

That might’ve been a mistake, though how I could have predicted trouble, after my bland first day, I don’t know.

The problem was at home I had nothing to distract me from—the button. I will call it that. My evening, usually dedicated to study (I have been reading the collected works of Georges Sand) quickly devolved into a nightmare, an endless oscillating loop between an increasingly urgent desire to push the button, just push it, just push the god damn button. Push. It. And an equally intense resistance that set itself up as a reverberating clamor in my brain that boomed the words as though from a train-station loudspeaker: what if it’s an off button?

And then I would think, don’t be ridiculous. It could as easily have been a button that did absolutely nothing. Or a button that got rid of my allergies, or my acid reflux, or my toe fungus.

Sleep was out of the question under these circumstances, and the night wore on, and I truly understood the night then, how we are, each of us, lowered in those late hours of dark and silence into its deep well, narrow and cold and dank, where we experience our own hopelessness and taste the awful cold and tainted water of death. I had the TV on, its cool bluish light washing across the room, a movie about some guy in a desert location with motorcycles, and it was then, and only then—I say this with certainty, since it struck me as very odd that it took this long to have such an obvious thought—yet I swear I had not had it until just that moment when I sat on my old easy chair in the den, hopeless in the deep well of night—that I had the thought: who the hell put it there? You see what I mean. Why had it taken this long to have this most obvious of all thoughts? I can’t answer the question. I told myself it had to do with my being one of those people who makes a conscientious effort to be forward-looking. But that sounded like bunkum, and before I could even start to evaluate, I found myself thinking once again, the thought like some invasion of ants crawling up my brainstem, push it, why don’t you just push it? And I could see that another casualty of this medical condition (for so it seemed this was) was that my new obsession made impossible higher order ethical reasoning.

But who did put it there? I quickly ran through the usual suspects that paranoia might suggest: the Obama administration; rogue CIA agents; thugs hired by that

Read More

There’s a scene in Proust that has stayed with me—though I would not perhaps say I’ve been haunted by it; more like, it has lingered on in some cork-lined closet at the back of my head, an on-again, off-again oscillation of long duration. The scene is found in Time Regained, the last volume of In Search of Lost Time, and follows the narrator as he departs from one of the novel’s most famous set pieces: his visit to a brothel in which he discovers Charlus, who broods over In Search of Lost Time the way Satan broods over Paradise Lost, in flagrante delicto.

The narrator walks out into the street from the claustrophobia of the house of prostitution, in which the distorting effects of love and desire have been on display, into the Paris of World War I, as an air raid begins. The streets are suddenly plunged in darkness, antiaircraft guns begin to fire, and it’s even possible, because the narrator is now a few blocks away, that a bomb has fallen on the brothel itself. That bomb, those bombs, falling without warning from the night sky, metaphorically represent love itself, and the entire scene—the plunge into darkness, the sudden appearance of incendiary danger out of the sky, the illumination of the explosions––maps the human experience of desire and love.

The narrator is struck by how little those who are pursuing their pleasures would be distracted by the dangers of falling bombs. “Seldom do we take any note of the social setting or the natural surroundings in which our love affairs are placed. The tempest rages at sea, the ship rolls in every direction, torrents of rain, whipped by the wind, pour down from the sky: we give heed for just an instant––and then only to protect ourselves against some inconvenience it is causing us––to the immense scene in which we and the beloved body we are clasping close are but insignificant atoms.”

It boosts semen load and helps to enjoy intimate moments with their partner, but due to erotic dysfunction of her partner, she always left unsatisfied eroticly which affect them psychologically. purchase viagra uk But experts donssite.com generico levitra on line suggest that men should not feel low since it is a treatable condition and is not unusual. Many chiropractic offices have a massage therapist that can help de stress the body, increase circulation, which then facilitates the movement of oxygen and remove other psychological problems such as stress, confusion, depression, stress and anxiety- Feeling stressed, low and anxious leaves direct impact over the potency acquisition de viagra and desire. Relating to mononuclear viagra online from canada cells, intracerebral, intraspinal and intrathecal administration have worked out.

The metaphor’s power at least partly derives from its fluctuation between its literal and figurative senses. The “immense scene” which forms the backdrop of love is the world and all its immediate dangers. But the “immense scene” is also metaphorically love and desire itself, the dangerous threat that turns the ordered world upside down, erasing external reality the way darkness in a blackout erases the city, and falling upon the unsuspecting flâneur like the explosives pitched from the cockpits of German biplanes. These are literal Gothas dropping bombs on Paris, but they are also representations of the violence and unexpectedness of love which strikes us as though the sky is falling, and meanwhile, we, like blind molds on our urgent business, ignore the very landscape in which we are encased—we, the “insignificant atoms” of the metaphor caught within prodigious geographies of desire.

Proust’s metaphor is like one of those massively complex atoms created in cyclotrons that disintegrates radioactively in milliseconds; in that way, it further reflects the paradox of human passion through the transient glimpse it offers of its ever vanishing essence—an essence that drives and determines us even as we fail to locate it except in the complex and inevitably disintegrating metaphors that artists create in homage to it—and so, yes, perhaps haunted was the right word after all.

Read More

I attended a christening on Sunday at a church on 49th St. in Manhattan in the Theater District near Times Square, the church named after St. Malachy, who it turns out is the patron saint of actors. I got there a few minutes late, and the place was packed—I thought at first with friends of the family, but the church attracts

many tourists in New York to see a show—so I stood by the back door and watched the proceedings from there.

My location I figured was probably good, since the baptismal font was stationed in the main aisle only a few feet from me. Things started out fine. But then someone opened the door behind me, a blast of cold air struck my neck, and I turned to watch as a very small woman with a mane of black swept-back hair entered the church.

It took me a second to realize that she was holding a parrot perched on her hand.

I normally don’t mind birds. As I’ve grown older I’ve experienced a growing and eager fondness for anything that’s alive at all—for obvious reasons. The parrot was not large either and seemed well behaved— although was that the nub end of a hot dog the woman was holding between her fingers and from which the bird was pecking and tearing off bits? Are parrots carnivores, I wondered? And then there was the question of what kind of parrot. I’m no expert. The parrot was mostly green but had a distinctive black head, and I wondered if it weren’t a black-headed conure, a rare bird in New York that’s more frequently observed in Southern Ontario.

Right now, probiotic use is being clinically shown to improve intestinal conditions, such as irritable cialis professional cheap bowel syndrome (IBS), colitis and Crohn’s disease (CD). viagra 25 mg Try one and get the change. levitra discount prices In fact it is a major communal, monetary, and a municipal health hazard. It also improves pastilla levitra 10mg the blood flow to the penile area.

Then there was the more disturbing question. What was the woman planning to do with the parrot? Baptize it? For what other reason would one bring a parrot to a christening? Companionship? The service proceeded, the time of the christening arrived. My friend’s beautiful daughter was duly held up in her exquisite white dress and water dabbed on her head. My view was good, though a crush of people arrived from other parts of the church to mar it slightly, and in the meantime, despite my worry, I must have been swept up in the moment; I lost sight of the woman with the parrot.

The baptism was done, people soon returned to their seats, and it was then I again caught sight of the woman. She had moved to the other side of the aisle and was now near the rear line of pews. But what was particularly disconcerting was that she no longer had the parrot!

You can imagine what I must have thought. Had this sick, tortured being drowned the parrot in the baptismal font in the confusion surrounding the legitimate baptism of the child? This is New York after all. Times Square. I considered going to the baptismal font to investigate, but the idea of finding the drowned form of the bird lying in the water was a shock I wasn’t prepared to withstand. And so I did what I always do when I’m not certain what to do. I did nothing.

The service proceeded but I couldn’t help but throw a few looks in the direction of the woman, who was nonetheless all piety. What was her game, I kept wondering? The service passed in this fashion. Now the minister was giving the final benediction. People were turning to go, but wait: the woman was coming toward me, and the parrot was back, perched on her shoulder. What had she done with it during its absence? Had it flown to a rafter for a better view? I was baffled until I saw the bird hop with expert skill from her shoulder and across her shirt, and then poking his head into opening above her shirt’s top button, simply crawl inside, disappearing within. She gave me a look, the woman with the parrot in her shirt, that seemed to contain within it some reluctant acceptance that something embarrassing, but also necessary and unavoidable, had just happened, and that this was not the first time. I can only say that the sight of the bird’s tail as it poked out of the shirt for an instant and then disappeared held a peculiar horror for me. It must have been some childish sensation that the parrot in merely hiding inside her shirt was actually going inside her. My sense of horror augmented. I felt stifled in the press of the crowd, and I quickly made my way outside in the cold clear morning of midtown New York.

Read More