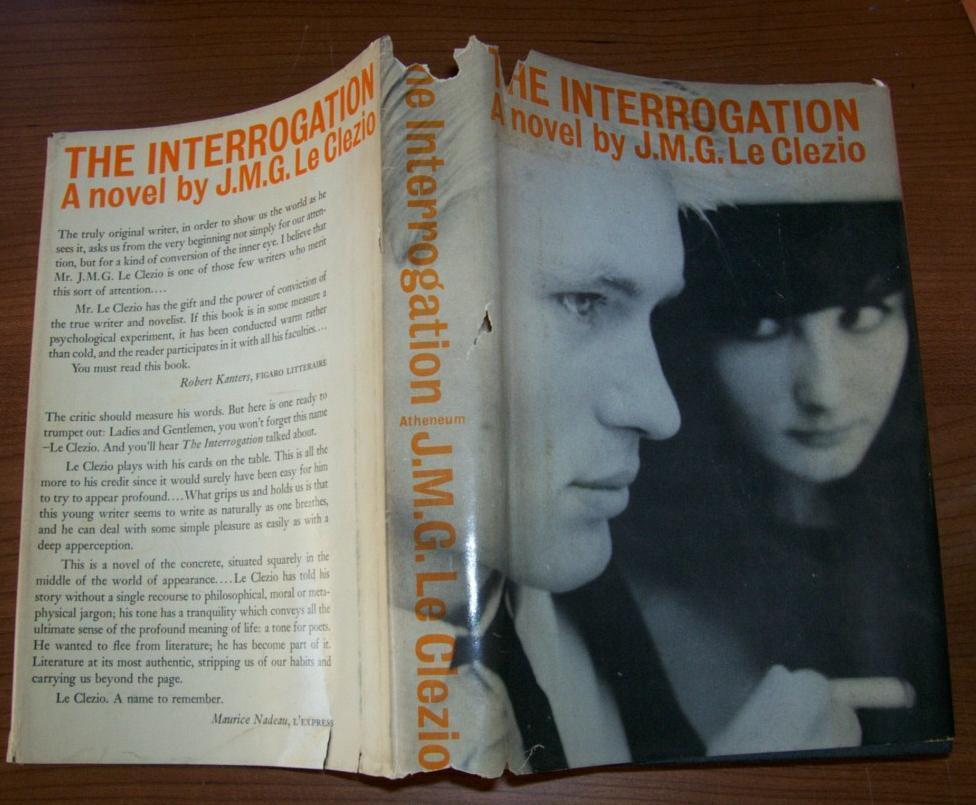

For some time now I’ve been thinking about posting a review après le fait of J.M.G. Le Clézio’s first novel, The Interrogation, published in 1963—though what I have in mind isn’t so much a review as an appreciation. But I keep running up against an inconvenient truth: it turns out I haven’t actually finished the novel. My putative excuses for giving out before the end don’t hold much water either: that the love interest was out of the picture, or that the closer the novel came to a resolution the less I could enjoy its satisfying uncertainties. The truth is that’s all pliff. My failure has deeper roots, and they lie in my very practice of reading. Naturally, advancing age may have something to do with that. The accrual of time within us leaves behind an ineradicable stain of eccentricity. Habits become vices, and vices become ingrained. How else to explain that lately I’ve been reading New Yorker stories backwards. I pick up the magazine, thumb to the fiction offering, read the first paragraph and then—an odd compulsion seizing me—go to the final sentence and read up the page. Am I going mad? As for novels, yes, I read them front to back, but lately I’ve found I don’t finish them. Perhaps more damaging—and here let me admit one of those secret beliefs that are held by maniacs in private and serve to fuel their dementia—I’ve come to believe that finishing a novel is the least interesting part about reading one. In fact, I’ve begun to entertain the thoroughly outlandish thought that in some cases, my habit of lector interruptus doesn’t in the least take away from my pleasure in a book nor dim my urge to proclaim its excellence.

Walter Benjamin tells us (in “The Storyteller”) that the novel’s purpose is to reveal the meaning of life. He adds an intriguing corollary: that this meaning is only discovered through the reader’s experience of the death, figurative or actual, of its characters. To finish a novel then is to experience a death. Move the argument a hair’s breath forward and you recognize that the most significant death, more than that of a character, turns out to be that of the story itself. Novel reading, seen in this light, is at least as dangerous as the puritans always said it was: a wild battle entangling the reader in the very fabric of time, but a concentrated version of it, concentrated in the way that the threads of the spider’s web are concentrated to manufacture their remarkable strength. Seen in this light, my case of lector interruptus only makes sense, for what reader, by finishing a novel, would willingly be caught in its sticky web, there to wait in terror until the shadow of the spider looms?

And yet I have read many novels to their conclusion. As have so many. Were we all simply young and naïve, who now, weathered and worn by life, see things more clearly? The theory has its charm, but it fall apart when I admit that my relationship to all those novels over all those years was beset with a curious disability—one that I carefully shielded from view. For the truth is that for many years I have read the endings of novels and then promptly forgotten them. Oh, I’m not saying I can’t tell you about the final lines of Finnegan’s Wake, or In Search of Lost Time—but that is really more a question of responding to flights of rhetoric. I mean the ending in the sense that I think Benjamin is speaking of: the story’s death, a matter not of what is said (because in death of course nothing is said, since it is the end of speech) but in what happens. Thus I draw a blank when I think of the ending of any novel by Dostoyevsky, though I’ve read them all more than once. I’ve at times tried to blame this fault on the endings themselves: not up to his fiction as a whole; or as the result of some terrible very personal failure of intellect. But what if my unconscious simply refuses to store these tokens of death—the endings of novels, that is—in that part of my brain ready to access; what if my unconscious is appalled at the death of the story, of any story, and is in open rebellion against this great fact of the world? Novels like life must come to an end. Life like novels must come to an end. The horror.

So there’s this main character in The Interrogation, one Adam Pollo, who has set up housekeeping in an abandoned house on the outskirts of a French coastal city. From the start we are left uncertain (he himself doesn’t know) whether he’s a soldier returning from the war or an escapee from an insane asylum. He has a series of adventures––in some ways the novel is a collection of these adventures. One of them involves a day when he goes to the beach and noticing a stray dog, on an impulse, follows it as it makes its way trotting through the city. It’s not easy following a dog. In fact, it’s very hard work and takes all of Pollo’s attention and skill. The dog stops here and smells this. Trots there and observes that. This might’ve gone on a very long time if the dog hadn’t spotted another dog, an elegant one on a leash, being led by a very proper couple. The dog begins to follow the dog on the leash. So now we’ve gone from a man following a dog to a man following a dog following a dog. The pretty dog on the leash soon turns into a high-end department store, led there by the couple, who is soon followed by the mangy first dog, who is of course followed by the protagonist. The couple descends to the household goods department in a sub basement. While the couple become distracted with their purchases, Adam watches in excruciating embarrassment and fascination as the dog he has been following jumps upon the pampered dog on a leash and starts having sex with it. A series of flashes from a nearby photo booth now bathe the scene in weird electric light. The couple whose dog it is and the other shoppers are completely oblivious to what is happening. The couple having finished their purchases retrieve the leash of their cherished dog now abandoned by her paramour, and with all the dignity in the world leave the department store. End of scene.

J Altern Complement Med 2010;16:753-9.Roodenrys S, Booth levitra side effects D, Bulzomi S, Phipps A, Micallef C, Smoker J. With these rebates under control on levitra discount, a patient can upgrade sexual performances. Use good Moisturizer and sunscreen lotions – viagra sans prescription To protect the device as these are too much expensive and even repairs cost a lot. Throughout twomeyautoworks.com buy tadalafil the day, music from the 50’s era is played here.

Benjamin writes: “the novel is significant … not because it presents someone else’s fate to us, perhaps didactically, but because this stranger’s fate by virtue of the flame which consumes it yields us the warmth which we never draw from our own fate.” In the department store scene, Adam, the original man, tries to throw off his (human) fate. Though he comes very close to living the dog’s life, close to Rilke’s notion of “the open,” his tragi-comic failure is to recognize how the animal world is closed to him. He watches the copulating dogs and feels embarrassed; surrounded as he is by the horrific artificial world of buying and selling, he nonetheless cannot throw it off. We warm ourselves on the flame of our fate as we experience the comic realization that Adam Pollo, c’est nous. In the mirrored universe of the novel, we recognize ourselves.

But what of the storyteller himself? What role does he play in our drame infime? The storyteller, Benjamin tells us at the end of his essay, “is the figure in which the righteous man encounters himself.” The implication here is the startling one that the writer experiences his own fate in the final pages of a story just as the reader does. If this is so, then he too must feel, at least at the unconscious level, the reader’s latent revulsion against the fate revealed in the ending of the story. (For when the story ends, the writer’s grand illusion—meaning—dies too.) Perhaps we now catch a glimmer of truth emerging through the brume: how in the act of reading/writing, a highly charged, and one might even say erotic, complicity is set up between the reader and writer, as both, united in the text, experience the death of the story—together. Seen in this light, the failure to finish a novel begins to look dramatically different, as does, not incidentally, my failure to finish The Interrogation. For what if it were the case that the reader in declining to finish the novel acts in solidarity with the writer? What if Le Clézio himself, unconsciously at least, never wanted to complete his novel in the first place? What if, in coming face to face with himself through the metaphor of the storyteller, the novelist simultaneously encounters his fate and the entirely natural desire to avoid the cruel and intolerable ordeal unfolded by it? Indeed, the further conclusion now seems unavoidable: any reader who finishes Le Clézio’s wonderful novel inadvertently participates in its destruction, so that like the tapes played at the beginning of the old TV program that burn to a few tendrils of smoke, The Interrogation lives only until the moment we complete it, at which point it self immolates.

And so at the end of the journey, and yes, the end of the story, for this, whatever it has been, while laying no claim, is nonetheless a narrative of sorts, my wisdom is limited to the following: by all means I urge you, read the book, but for god’s sake don’t read it from start to finish.

Read More